Ramblings from the AEO’s Panel – Part 20

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a

On 19 October 1945, just over two months after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, English writer George Orwell’s essay, “You and the Atomic Bomb” , was published in a British newspaper. This is thought to be the origin of the term ‘cold war’.

The Cold War was a period of tension between the Soviet Union and the United States and their respective allies. The term ‘cold’ is used because there was no direct fighting between the two superpowers. However, they opposed each other by supporting other conflicts known as proxy wars.

The Cold War and its events are often referred to with themes of espionage and the threat of nuclear warfare. Cold War Stories brings you some scarcely believable, but actually very true, stories from the era.

In the early 1950s a joint operation was conducted by the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the British MI6 Secret Intelligence Service. Operation Gold, as it was known by the US, or Operation Stopwatch as it was referred to by MI6, was to tap into the landline cables of the Soviet Army HQ in Berlin. The Soviets had moved their most secure communications from radio to landline and the joint operation would construct a tunnel twenty feet beneath the surface of Berlin, from the US sector of Altglienicke into the Soviet occupied side of the zone. The communications intercepted in the spy tunnel were to serve as an early warning system of Soviet intentions in Europe.

The idea mirrored a successful British effort in Austria, which is known as Operation Silver. The British had covertly tapped into the landline communications of the Soviet Army HQ in Vienna and the intelligence provided vital information during the Korean War.

As head of the MI6 station in Vienna, Peter Lunn discovered that beneath the French and British sectors, there were telephone cables that linked field units and airports of the Russian Army to Soviet HQ. The Soviets believed that the copper network buried in the ground could be used for their communications without danger. Lunn decided that by digging a tunnel, it would be possible to get under the switchboard and tap the telephone lines there.

The British bought a shop on a main street and tweed clothing was sold there as a cover for the operation. The clothing was so popular among the Austrians that the business even made a profit. A private house was also bought nearby to serve as the starting point for the tunnel. In 1949 the tunnel was completed.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the US had concerns about how much it could get involved in the war without irritating the Soviet Union too much. The information from the Vienna tunnel established that the Soviets were not interested in expanding the conflict to Europe at the time. This meant the American engagement in Korea could be expanded.

After several years of successful wiretapping, Operation Silver ended with the re-establishment of Austrian independence. Effectively there was no one left to tap.

Operation Silver only required a 70-foot-long tunnel, whereas the Berlin tunnel would need to be 1,476 feet long – 22 feet more than the height of the Empire State Building.

Peter Lunn became head of the MI6 station in Berlin, and co-operated with his CIA opposite number William King Harvey to plan the Berlin Tunnel. The operation was code named PBJOINTLY in official documents, with the P and B standing for Peter and Bill respectively.

A series of conferences between the US and Britain took place in late 1953 and early 1954. The decisions made were:

The U.S would:

The British would:

While planning the tunnel there was a realisation that there would be approximately 3,000 tons of soil excavated that needed disposing of in secret. In an originally classified document, a CIA engineer later noted that “rough calculations showed that the amount of soil expected to be brought out from the tunnel and vertical shaft would fill to the brim more than 20 living rooms in an average American home! Security and silence dictated that not one cubic foot of soil be removed from the site. A warehouse, with a basement for the storage of the excavated soil and a first floor reserved for recorders and signal equipment, was the solution.”

As a cover story, local engineers were told the warehouse was an experiment. Half of the building would be above ground and half below with a ramp to run forklifts from the basement to the first floor. They were told Berlin had been chosen because the labour rates were low so construction would be cheap, and the work would benefit the Berlin economy. The basement was able to be dug in plain sight of the border guards and provided the hole for the soil excavated from the tunnel.

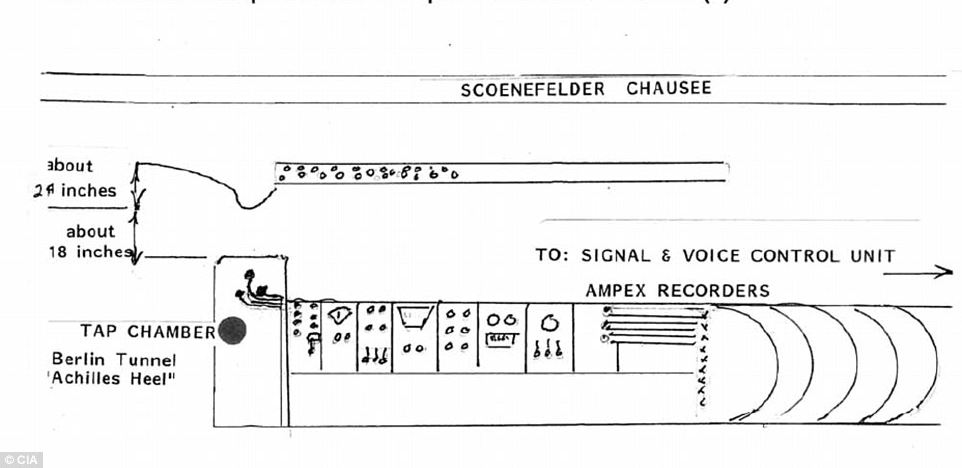

The tunnel was to cross the strictly guarded border at a depth of around 20 feet, and the cable to be tapped ran less than 20 inches below a busy street named Schönefelder Chaussee. The structural analysis of the tunnel build was sophisticated, as it had to withstand the possibility of Soviet and East German 60-ton tanks traveling across the land above the tunnel. It was a major engineering challenge made more difficult by an unexpected leak when the diggers encountered ground water at 16 feet while digging the vertical shaft, instead of the predicted 32 feet. A clay lens existed that created a perched water table in that spot. Pumps were installed to remove the excess water and the dig continued.

Work on the tunnel dig began in August 1954 and was completed some six months later on 28 February 1955. Construction of the tap chamber began on 10 March and the three target cables were tapped on 11 May, 21 May and 2 August 1955. The equipment was all in place so that monitoring could begin as soon as the cables were tapped.

On 22 April 1956, after 11 months and 11 days of operation, the tunnel was discovered by the Soviets. A CIA report at the time details that it was thought the tunnel was discovered because of heavy rainfall entered a faulty cable, causing sections of the cable to be dug up for repair. In doing this the Soviets discovered the tap into their line. However, MI6 later discovered that a case officer named George Blake had been recruited by the KGB while he was a prisoner in North Korea.

In 1953, following his release as a prisoner of war, Blake returned to Britain as a hero and continued his career with MI6. He attended the initial Berlin tunnel meeting in London between the CIA and MI6, taking the detailed minutes. When Blake next met his KGB contact, he handed him a copy of the minutes from the meeting and a very small sketch, which he drew himself, of how the cable would run, how the tunnel would run and which cables it would carry.

In 1955 MI6 sent him to work in Berlin for Peter Lunn . Blake’s task wasn’t the Berlin tunnel, but to recruit Soviet officers as double agents. While in this post he gave the Soviets details of the 400 MI6 agents working in Germany.

The Soviets allowed the tunnel to be dug and operated for nearly a year before ‘discovering’ it. The KGB didn’t use the tapped lines to spread disinformation. They kept the flow of information as normal as possible to protect their asset – Blake. Also, they were unwilling to share their secrets with rival agencies internally and with their allies, so they didn’t inform the Soviet’s Main Intelligence Directorate – the GRU, or Germany’s Ministry for State Security – the Stasi, who both carried on freely discussing information on the tapped lines. The KGB’s own high-level communications went on a separate system of overhead lines that could not be tapped without it being obvious.

On discovering the tunnel, Soviet and East German soldiers broke into the eastern end and invited the entire Berlin press corps to a briefing. On Monday 23 April 1956, the acting military commander of the Soviet sector of Berlin, Colonel Kozjuba, announced at a press conference that Soviet troops had dug up an American eavesdropping centre. Following the press conference, a tour of the tunnel took place.

The Soviets announced the espionage to the press as a “breach of the norms of international law” and “a gangster act”. Newspapers around the world ran photographs of the underground partition of the tunnel directly under the inter-German frontier. The Soviets had hoped to win a propaganda victory in publicising the tunnel and painting the US in a dark light to the world. However, the ingenuity of the US-UK operation was acclaimed around the world.

The total cost of the project was $6.7m, which is the equivalent of over $64m today (2020). During the operation a vast amount of intelligence was intercepted via the taps. The London processing centre employed 317 people and 443,000 conversations had to be transcribed from the voice reels that were obtained. The Washington centre employed 350 people and 29,000 six-hour teletype reels had to be transcribed. The backlog of material continued to be processed until September 1958.

Many details of the operation are still classified, but a CIA report written in 1967 was largely declassified in 2007. The report includes details of an assessment written in 1956 after the discovery of the tunn el. The assessment details events from Monday 16 April to Sunday 22 April 1956, the day that the wire taps were cut.

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a key

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a

The July 1945 General Election saw a Labour Government come to power in a landslide victory under Prime Minister Clement Attlee. The use of two