A Brief History of the Falkland Islands

On 2 April 1982, Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands. It was the beginning of a ten-week conflict that ended with the Argentines surrendering

In March 2019, the Vulcan to the Sky Trust were privileged to organise a special evening in the wonderful surroundings of Gatwick Aviation Museum. The guest speaker was Ian Whittle, son of Sir Frank Whittle – the greatest aero-engineer of the twentieth century. Ian gave a presentation on his father’s childhood and the influence early aviation pioneers had on him in seeking a career in the RAF.

Ian’s talk featured the full story of jet turbine development and the various struggles faced by his father.

In the audience that night was John Falk, grandson of O. T. Falk and son of ‘Roly’ Falk. The latter name will be well known to aviation enthusiasts as a British test pilot. One of Roly’s many test flight achievements was making the maiden flight of the Avro Type 698 – the Vulcan. The story of Frank Whittle reveals a connection between Frank and Roly’s father, O.T. Falk.

In Part 1 of the Whittle and the Power Jets story, Ian tells how his father progressed through the RAF, developed his ideas and eventually met key people who would help him develop what we know today – the modern jet engine.

In January 1923, having passed the RAF entrance examination with a high mark, Whittle reported to RAF Halton as an Aircraft Apprentice. He lasted only two days: just five feet tall and with a small chest measurement, he failed the medical. He then put himself through a rigorous training programme and special diet devised by a physical training instructor at Halton to build up his physique, only to fail again six months later, when he was told that he could not be given a second chance, despite having added three inches to his height and chest. Undeterred, he applied again under an assumed name and presented himself as a candidate at the No 2 School of Technical Training RAF Cranwell. This time he passed the physical and, in September that year, 364365 Boy Whittle, F started his three-year training as an aircraft mechanic in No. 1 Squadron of No. 4 Apprentices Wing, RAF Cranwell, because RAF Halton No. 1 School of Technical Training was unable to accommodate all the aircraft apprentices at that time.

Whittle hated the strict discipline imposed on apprentices and, convinced there was no hope of ever becoming a pilot he at one time seriously considered deserting. However, throughout his early days as an aircraft apprentice (and at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell), he maintained his interest in model aircraft and joined the Model Aircraft Society, where he built working replicas. The quality of these attracted the eye of the Apprentice Wing commanding officer, who noted that Whittle was also a mathematical genius. He was so impressed that in 1926 he recommended Whittle for officer training at RAF College Cranwell.

For Whittle, this was the chance of a lifetime, not only to enter the commissioned ranks but also because the training included flying lessons on the Avro 504. While at Cranwell he lodged in a bungalow at Dorrington. Being an ex-apprentice amongst a majority of ex-public schoolboys, life as an officer cadet was not easy for him, but he nevertheless excelled in the courses and went solo in 1927 after only 13.5 hours instruction, quickly progressing to the Bristol Fighter and gaining a reputation for daredevil low flying and aerobatics.

A requirement of the course was that each student had to produce a thesis for graduation: Whittle decided to write his on potential aircraft design developments, notably flight at high altitudes and speeds over 500 mph (800 km/h). In Future Developments in Aircraft Design, he showed that incremental improvements in existing propeller engines were unlikely to make such flight routine. Instead, he described what is today referred to as a motorjet; a motor using a conventional piston engine to provide compressed air to a combustion chamber whose exhaust was used directly for thrust – essentially an afterburner attached to a propeller engine. The idea was not new and had been talked about for some time in the industry, but Whittle’s aim was to demonstrate that at increased altitudes the lower outside air pressure would increase the design’s efficiency. For a long-range flight, using an Atlantic-crossing mail plane as his example, the engine would spend most of its time at high altitude and thus could outperform a conventional power plant

Of the few apprentices accepted into the Royal Air Force College, Whittle graduated in 1928 at the age of 21 and was commissioned as a Pilot Officer. He ranked second in his class in academics, won the Andy Fellowes Memorial Prize for Aeronautical Sciences for his thesis, and was described as an “exceptional to above average” pilot. However, his flight logbook also showed numerous red ink warnings about showboating and overconfidence and because of dangerous flying in an Armstrong Whitworth Siskin, he was disqualified from the end of term flying contest.

Whittle continued working on the motorjet principle after his thesis work but eventually abandoned it when further calculations showed it would weigh as much as a conventional engine of the same thrust. Pondering the problem he thought: “Why not substitute a turbine for the piston engine?” Instead of using a piston engine to provide the compressed air for the burner, a turbine could be used to extract some power from the exhaust and drive a similar compressor to those used for superchargers. The remaining exhaust thrust would power the aircraft.

On 27 August 1928, Pilot Officer Whittle joined No. 111 Squadron, Hornchurch, flying Siskin IIIs. His continuing reputation for low flying and aerobatics provoked a public complaint that almost led to his being court-martialled. Within a year he was posted to Central Flying School, Wittering, for a flying instructor’s course. He became a popular and gifted instructor and was selected as one of the entrants in a competition to select a team to perform the “crazy flying” routine in the 1930 Royal Air Force Air Display at RAF Hendon. He destroyed two aircraft in accidents during rehearsals but remained unscathed on both occasions. After the second incident, an enraged Flight Lieutenant Harold W. Raeburn said furiously, “Why don’t you take all my bloody aeroplanes, make a heap of them in the middle of the aerodrome and set fire to them – it’s quicker!”

Whittle showed his engine concept around the base, where it attracted the attention of Flying Officer Pat Johnson, formerly a patent examiner. Johnson, in turn, took the concept to the commanding officer of the base. This set in motion a chain of events that almost led to the engines being produced much sooner than actually occurred.

Earlier, in July 1926, A. A. Griffith had published a paper on compressors and turbines, which he had been studying at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE). He showed that such designs up to this point had been flying “stalled”, and that by giving the compressor blades an aerofoil-shaped cross-section their efficiency could be dramatically improved. The paper went on to describe how the increased efficiency of these sorts of compressors and turbines would allow a jet engine to be produced, although he felt the idea was impractical, and instead suggested using the power as a turboprop. At the time most superchargers used a centrifugal compressor, so there was limited interest in the paper.

Encouraged by his commanding officer, in late 1929 Whittle sent his concept to the Air Ministry to see if it would be of any interest to them. With little knowledge of the topic, they turned to the only other person who had written on the subject and passed the paper on to Griffith. Griffith appears to have been convinced that Whittle’s “simple” design could never achieve the sort of efficiencies needed for a practical engine. After pointing out an error in one of Whittle’s calculations, he went on to comment that the centrifugal design would be too large for aircraft use and that using the jet directly for power would be rather inefficient. The RAF returned his comment to Whittle, referring to the design as being “impracticable”.

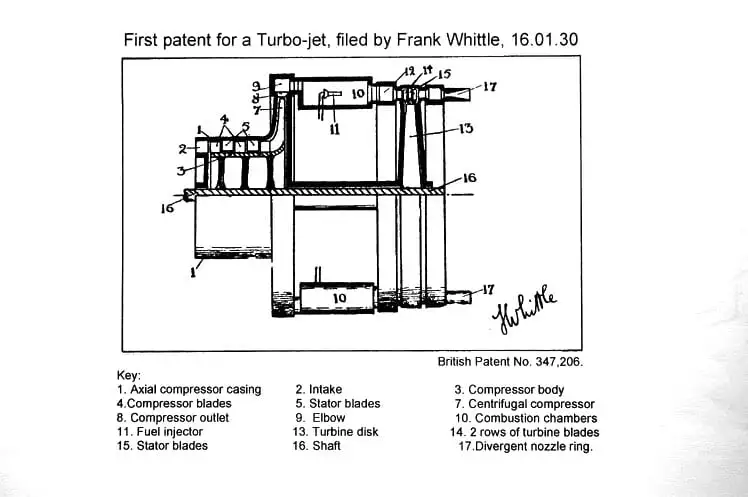

Pat Johnson remained convinced of the validity of the idea and had Whittle patent the idea in January 1930. Since the RAF was not interested in the concept they did not declare it secret, meaning that Whittle was able to retain the rights to the idea, which would have otherwise been their property. Johnson arranged a meeting with British Thomson-Houston (BTH), whose chief turbine engineer seemed to agree with the basic idea. However, BTH did not want to spend the ₤60,000 it would cost to develop it, and this potential brush with early success went no further.

In January 1930, Whittle was promoted to Flying Officer. In Coventry, on 24 May 1930, Whittle married his fiancée, Dorothy Mary Lee, with whom he later had two sons, David and Ian. Then, in 1931, he was posted to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe as an armament officer and test pilot of seaplanes, where he continued to publicize his idea. This posting came as a surprise for he had never previously flown a seaplane, but he nevertheless increased his reputation as a pilot by flying some 20 different types of floatplanes, flying boats, and amphibians.

Every officer with a permanent commission was expected to take a specialist course, and as a result, Whittle attended the Officers’ Engineering Course at RAF Henlow, Bedfordshire in 1932. He obtained an aggregate of 98% in all subjects in his exams, completing the course in 18 months instead of the more normal two years.

His performance in the course was so exceptional that in 1934 he was permitted to take a two-year engineering course as a member of Peterhouse, the oldest college of Cambridge University, graduating in 1936 with a First in the Mechanical Sciences Tripos. In February 1934, he had been promoted to the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

Power Jets Ltd

Still at Cambridge, Whittle could ill afford the £5 renewal fee for his jet engine patent when it became due in January 1935, and because the Air Ministry refused to pay it the patent was allowed to lapse.

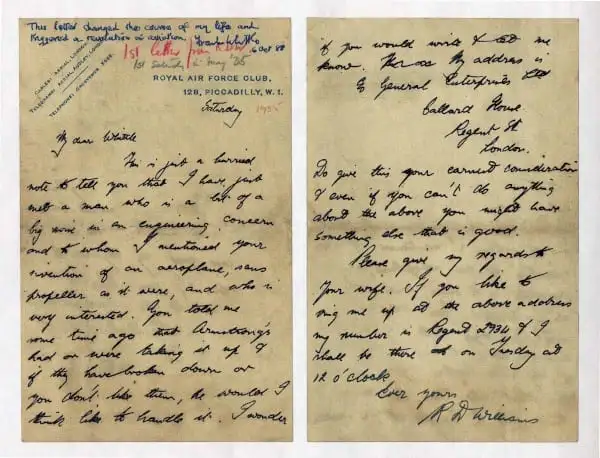

Shortly afterwards, in May, he received mail from Rolf Dudley-Williams, who had been with him at Cranwell in the 1920s and Felixstowe in 1930. Williams arranged a meeting with Whittle, himself, and another by-then-retired RAF serviceman, James Collingwood Tinling. The two proposed a partnership that allowed them to act on Whittle’s behalf to gather public financing so that development could go ahead.

The agreement soon bore fruit, and in 1935, through Tinling’s father, Whittle was introduced to Mogens L. Bramson, a well-known independent consulting aeronautical engineer. Bramson was initially sceptical but after studying Whittle’s ideas became an enthusiastic supporter. Bramson introduced Whittle and his two associates to the investment bank O.T. Falk & Partners, where discussions took place with Lancelot Law Whyte and occasionally Sir Maurice Bonham-Carter. (Another famous name in finance and grandfather of the actress Helena-Bonham Carter.)

The firm had an interest in developing speculative projects that conventional banks would not touch. Whyte was impressed by the 28-year-old Whittle and his design when they met on 11 September 1935.

“The impression he made was overwhelming, I have never been so quickly convinced, or so happy to find one’s highest standards met… This was genius, not talent. Whittle expressed his idea with superb conciseness.

Reciprocating engines are exhausted. They have hundreds of parts jerking to and fro, and they cannot be made more powerful without becoming too complicated. The engine of the future must produce 2,000 hp with one moving part: a spinning turbine and compressor.”

Lancelot Law Whyte on his first meeting with Frank Whittle

However, O.T. Falk & Partners specified they would only invest in Whittle’s engine if they had independent verification that it was feasible. They financed an independent engineering review from Bramson – The historic “Bramson Report”, which was issued in November 1935. It was favourable and Falk then agreed to finance Whittle. With that, the jet engine was finally on its way to becoming a reality.

On 27 January 1936, the principals signed the “Four Party Agreement”, creating “Power Jets Ltd” which was incorporated in March 1936. The parties were O.T. Falk & Partners, the Air Ministry, Whittle and, together, Williams and Tinling. Falk was represented on the board of Power Jets by Whyte as Chairman and Bonham-Carter as a director (with Bramson acting as an alternate). Whittle, Williams and Tinling retained a 49% share of the company in exchange for Falk and Partners putting in £2,000 with the option of a further £18,000 within 18 months.

As Whittle was still a full-time RAF officer and currently at Cambridge, he was given the title “Honorary Chief Engineer and Technical Consultant”. Needing special permission to work outside the RAF, he was placed on the Special Duty List and allowed to work on the design as long as it was for no more than six hours a week. However, he was allowed to continue at Cambridge for a year doing post-graduate work which gave him time to work on the turbojet.

The Air Ministry still saw little immediate value in the effort (they regarded it as long-range research), and having no production facilities of its own, Power Jets entered into an agreement with steam turbine specialists British Thomson-Houston (BTH) to build an experimental engine facility at a BTH factory in Rugby, Warwickshire.

On 2 April 1982, Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands. It was the beginning of a ten-week conflict that ended with the Argentines surrendering

An unexpected gift from his wife for his birthday changed ex RAF and Red Arrows engineer, Tony Sykes and his son, Connors lives overnight. The

On 16 July 1945, with the support of Britain, the United States detonated the world’s first atomic weapon. In August 1949, the USSR successfully tested

On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union began the Space Age by launching Sputnik 1. It was the world’s first artificial satellite – so called