Ramblings from the AEO’s Panel – Part 17

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a

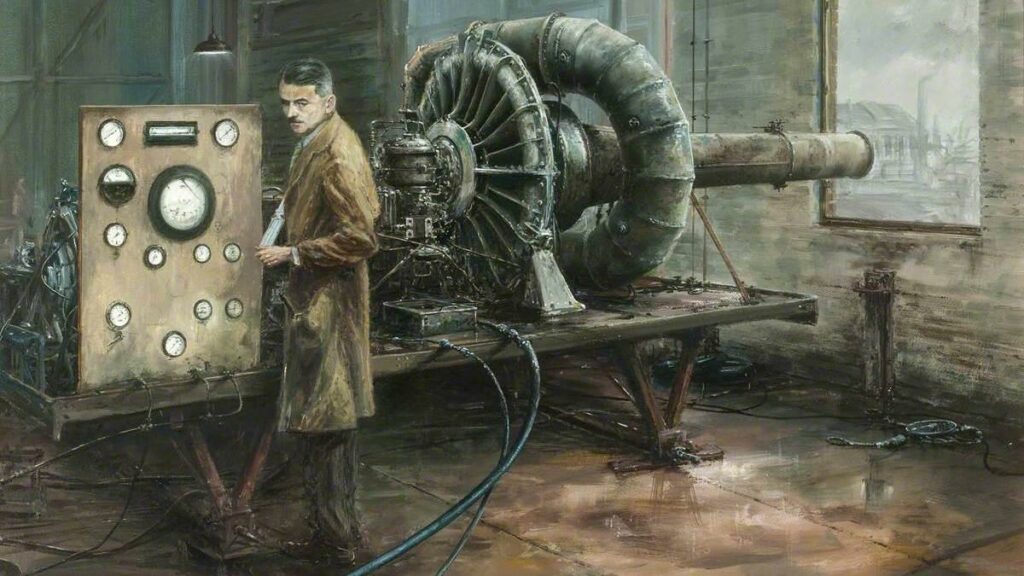

In January 1936, when the Power Jets company was created, Henry Tizard, the rector of Imperial College London and chairman of the Aeronautical Research Committee (ARC), had prompted the Air Ministry’s Director of Scientific Research to ask for a write-up of the design. The report was once again passed on to their technical representative, Griffith, for comment, but was not received back until March 1937 by which point Whittle’s design was well along.

Griffith had already started construction of his own turbine engine design and, perhaps to avoid tainting his own efforts, he returned a somewhat more positive review. However, he remained highly critical of some features, notably the use of jet thrust. The Engine Sub-Committee of ARC studied Griffith’s report, and decided to fund his effort instead.

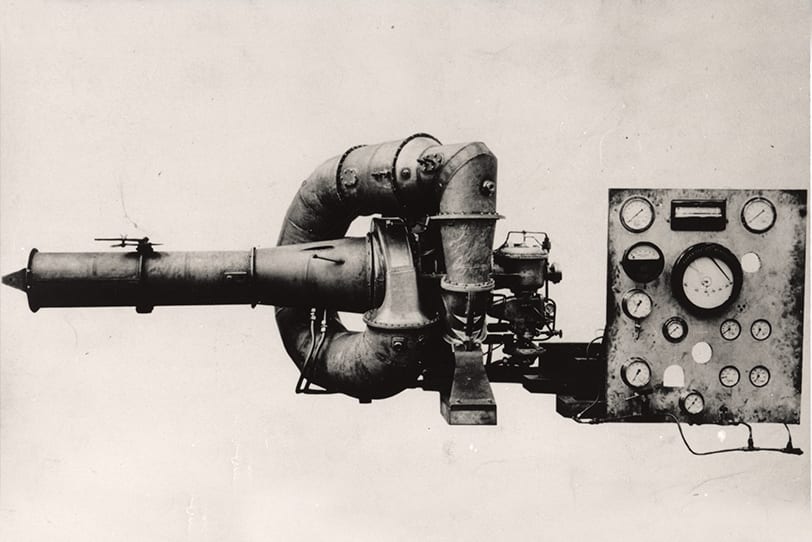

Given this astonishing display of official indifference, Falk and Partners gave notice that they could not provide funding beyond £5,000. Nevertheless, the team pressed ahead, and the W.U. (Whittle Unit) engine ran successfully on 12 April 1937. Tizard pronounced it “streaks ahead” of any other advanced engine he had seen, and managed to interest the Air Ministry enough to fund development with a contract for £5,000 to develop a flyable version. However, it was a year before the funds were made available, greatly delaying development.

In July, when Whittle’s stay at Cambridge was over, he was released to work full-time on the engine. On 8 July Falk gave the company an emergency loan of £250, and on the 15th they agreed to find £4,000 to £14,000 in additional funding. The money never arrived and, entering into default, Falk’s shares were returned to Williams, Tinling and Whittle on 1 November. Nevertheless, Falk arranged another loan of £3,000, and work continued. Whittle was promoted to Squadron Leader in December.

Testing continued with the W.U., which showed an alarming tendency to race out of control. Because of the dangerous nature of the work being carried out, development was largely moved from Rugby to the British Thompson-Houston’s (BTH) lightly used Ladywood foundry at nearby Lutterworth in Leicestershire in 1938, where there was a successful run of the W.U. in March that year. BTH had decided to put in £2,500 of their own in January, and in March 1938 the Air Ministry funds finally arrived. This proved to be a mixed blessing – the company was now subject to the Official Secrets Act, which made it extremely difficult to gather more private equity.

These delays and the lack of funding slowed the project. In Germany, Hans von Ohain had started work on a prototype in 1935, and had by this point passed the prototype stage and was building the world’s first flyable Jet aircraft, the Heinkel HeS 3. There is little doubt that Whittle’s efforts would have been at the same level or even more advanced had the Air Ministry taken a greater interest in the design. When war broke out in September 1939, Power Jets had a payroll of only 10 and Griffith’s operations at the RAE and Metropolitan-Vickers were similarly small.

The stress of the continual on-again-off-again development and problems with the engine took a serious toll on Whittle.

His smoking increased to three packs a day and he suffered from various stress-related ailments such as frequent severe headaches, indigestion, insomnia, anxiety, eczema and heart palpitations, while his weight dropped to nine stone (126 lb / 57 kg). In order to keep to his 16-hour workdays, he sniffed Benzedrine during the day and then took tranquillizers and sleeping pills at night to offset the effects and allow him to sleep. He admitted later he had become addicted to benzidine. Over this period he became irritable and developed an “explosive” temper.

Changing fortunes at last

By June 1939, Power Jets could barely afford to keep the lights on when yet another visit was made by Air Ministry personnel. This time Whittle was able to run the W.U. at high power for 20 minutes without any difficulty. One of the members of the team was the Director of Scientific Research, David Randall Pye, who walked out of the demonstration utterly convinced of the importance of the project. The Ministry agreed to buy the W.U. and then loan it back to them, injecting cash, and placed an order for a flyable version of the engine.

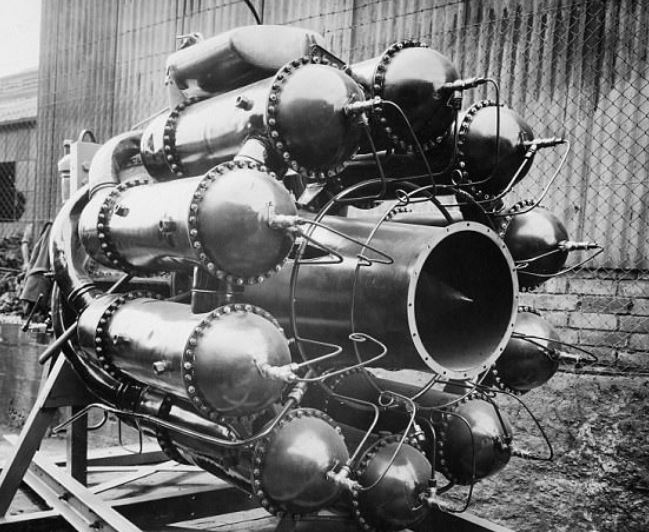

Whittle had already studied the problem of turning the massive W.U. into a flyable design, with what he described as very optimistic targets, to power a little aeroplane weighing 2,000 lb with a static thrust of 1,389 lb. With the new contract work started in earnest on the “Whittle Supercharger Type W.1”. It featured a reverse-flow design; air from the compressor was fed rearwards into the combustion chambers, then back towards the front of the engine, then finally reversing again into the turbine. This design reduced the length of the engine, and the length of the drive shaft connecting the compressor and turbine, thus reducing weight.

In January 1940, the Ministry placed a contract with the Gloster Aircraft Company for a simple aircraft specifically to flight-test the W.1, the Gloster E.28/39. They also placed a second engine contract, this time for a larger design that developed into the otherwise similar W.2. In February work started on a third design, the W.1A, which was the size of the W.1 but used the W.2’s mechanical layout. The W.1A allowed them to flight test the W.2’s basic mechanical design in the E.28/39. Power Jets also spent some time in May 1940 drawing up the W.2Y, a similar design with a “straight-through” airflow that resulted in a longer engine and, more critically, a longer driveshaft but having a somewhat simpler layout. To reduce the weight of the driveshaft as much as possible, the W.2Y used a large diameter, thin-walled, shaft almost as large as the turbine disc, “necked down” at either end where it connected to the turbine and compressor.

In April, the Air Ministry issued contracts for W.2 production lines with a capacity of up to 3,000 engines a month in 1942, asking BTH, Vauxhall and the Rover Company to join. However, the contract was eventually taken up by Rover only. In June, Whittle received a promotion to Wing Commander.

Rover becomes involved

Meanwhile, work continued with the W.U., which eventually went through nine rebuilds in an attempt to solve the combustion problems that had dominated the testing. On 9 October the W.U. ran once again, this time equipped with Lubbock or “Shell” atomizing-burner combustion chambers. Combustion problems ceased to be an obstacle to the development of the engine although intensive development was started on all features of the new combustion chambers.

By this point, it was clear that Gloster’s first airframe would be ready long before Rover could deliver an engine. Unwilling to wait, Whittle cobbled together an engine from spare parts, creating the W.1X (“X” standing for “experimental”) which ran for the first time on 14 December 1940. On 10 December Whittle suffered a nervous breakdown and left work for a month. Shortly afterwards, an application for a US patent was made by Power Jets for an “Aircraft propulsion system and power unit”.

The W1X engine powered the E.28/39 for taxi testing on 7 April 1941 near the factory in Gloucester, where it took to the air for two or three short hops of several hundred yards at about six feet from the ground.

The definitive W.1 of 850 lbf (3.8 kN) thrust ran on 12 April 1941, and on 15 May the W.1-powered E.28/39 took off from Cranwell at 7:40 pm, flying for 17 minutes and reaching a maximum speed of around 340 mph (545 km/h). At the end of the flight, Pat Johnson, who had encouraged Whittle for so long said to him, “Frank, it flies.” Whittle replied, “Well, that’s what it was bloody well designed to do, wasn’t it?”

Within days the aircraft was reaching 370 mph (600 km/h) at 25,000 feet (7,600 m), exceeding the performance of the contemporary Spitfires. The success of the design was now evident; the first example of what was a purely experimental and entirely new engine design was already outperforming one of the best piston engines in the world, an engine that had five years of development and production behind it, and decades of engineering. Nearly every engine company in Britain then started its own crash efforts to catch up with Power Jets.

In 1941 Rover set up a new laboratory for Whittle’s team along with a production line at their unused Barnoldswick factory, but by late 1941, it was obvious that the arrangement between Power Jets and Rover was not working. Whittle was frustrated by Rover’s inability to deliver production-quality parts, as well as with their attitude of engineering superiority, and became increasingly outspoken about the problems. Rover decided to set up secretly a parallel effort with their own engineers at Waterloo Mill, in nearby Clitheroe. Here Adrian Lombard started work developing the W.2B into Rover’s own production-quality design, dispensing with Whittle’s “reverse-flow” combustion chambers and developing a longer but simpler “straight-through” engine instead. This was encouraged by the Air Ministry, who gave Whittle’s design the name “B.23”, and Rover’s became the “B.26”.

Work on all of the designs continued over the winter of 1941–42. The first W.1A was completed soon after, and on 2 March 1942, the second E.28/39 reached 430 mph (690 km/h) at 15,000 feet (4,600 m) on this engine. The next month work on an improved W.2B started under the new name, “W2/500”. In April Whittle learned of Rover’s parallel effort, creating discontentment and causing a major crisis in the programme. Work continued, however, and in September the first W2/500 ran for the first time, generating its full design thrust of 1,750 lbf (7.8 kN) the same day. Work started on further improvement, the W2/700.

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a

Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown is credited with over 2,400 carrier landings (no one else has come close) as well as being the holder of numerous ‘firsts’. He made

Research into delta-wing aircraft had also been conducted by the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, and the combined results of this programme and that

On 16 July 1945, with the support of Britain, the United States detonated the world’s first atomic weapon. In August 1949, the USSR successfully tested