Vulcan Camouflage – Adrian Sumner

I came across the story of how the Vulcan camouflage scheme originated, when I was on my first Vulcan tour as a co-pilot on IX

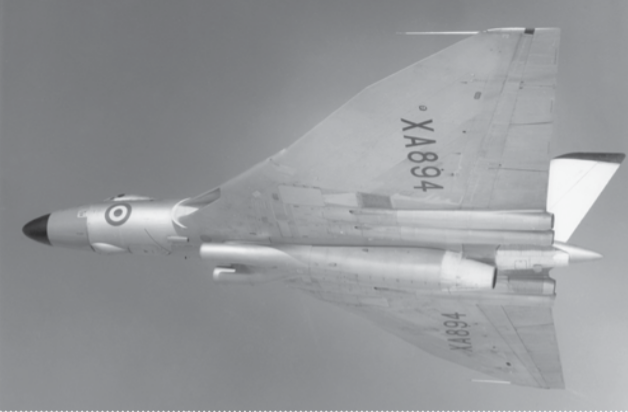

Aside from regular duties, several Vulcan airframes were put to use in test and development roles. XA894 spent all its life as a test aircraft, and was delivered to Filton in 1960, where the Olympus 22R (intended to power the TSR.2) was fitted into the bomb-bay. An engine explosion during ground running in December 1962 unfortunately destroyed the aircraft. Similarly, XA903 never entered operational service, being used for Blue Steel development initially, and the fitting of 27mm cannon. It then became an engine test-bed at Filton for the Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 engine that was to power Concorde, and then for the Turbo-Union RB199 for the Panavia Tornado (ironically the aircraft destined to be the Vulcan’s replacement).

As Soviet air defences improved it became clear there was a requirement for a weapons system with greater range than the 100 miles offered by Blue Steel. The Americans were developing a new air-launched ballistic missile for the B-52, the Douglas GAM-87A Skybolt, and the RAF planned to order it in place of the Blue Steel II then under development. Skybolt weighed 5 tons and was 38ft long, with a two-stage solid fuel motor designed to accelerate it to approximately 6,000mph (Mach 9) at a maximum height of 250 miles. It was guided by an astronavigation system, giving it an accuracy of a few hundred yards over its 1,000 mile range.

Vulcan B Mk.2’s from XL390 onwards had mounting points added under each wing – these later proved useful in the Falklands conflict for carrying Shrike missiles and the Westinghouse ECM pod. XH563 flew to the States in 1961 for electrical compatibility tests, with XH537 making the first drop (with dummy missiles), and XH538 carrying out aerodynamic trials during 1962. Avro test pilot Tony Blackman noted that air trapped between the missiles under the Vulcan’s large wing created a cushioning effect on landing.

Tests with the missile were problematic, with the first fully successful flight not occurring until December 1962, and this, together with arrival of the United States Navy’s Polaris missile, led to the US cancelling Skybolt. With the British government’s planned basis for its entire nuclear deterrent removed at a stroke, a storm of protest erupted in Parliament, leading to crisis talks between the two

governments. The Nassau Agreement resulted, whereby the UK would buy Polaris, but equipped with British warheads (and lacking the dual-key system), maintaining its independent deterrent.

In the early 1960’s, the main threat was perceived to be a pre-emptive strike by the Soviet Union. For the V-force to be a realistic deterrent, the aircraft had to be able to scramble within the 4 minute warning provided by the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System at RAF Fylingdales. For this reason Bomber Command, under Air Chief Marshal Sir Kenneth Cross, developed a QRA posture for the V-force. This meant crews living in huts close to Operational Readiness Platforms, where groups of Vulcans waited, fuelled and with pre-flight checks already completed, each armed with an 800 kiloton Yellow Sun nuclear free-fall weapon. The Vulcan B1 did not have the rapid start facility of the B2, but allowed the throttle positions to be pre-set and the engines started by the groundcrew, using the external ‘Simstart’ (simultaneous start) ground power unit as the crew arrived at the aircraft.

The whole reaction procedure was maintained and honed through regular practice and on one occasion at RAF Waddington, one of the pilots, the Commander of 101 Squadron, was having a shower when the alarm suddenly shattered the silence. There followed the usual mad scramble for the vehicles waiting to rush the crews on the short journey to their aircraft to meet the all important reaction time. The last to arrive was the wet pilot, still pulling on his flying suit. Waiting at the Vulcan, as the crew approached, was the crew chief ready to hit the Simstart button. As the damp pilot reached the aircraft’s entrance, he shouted to his co-pilot for the door key (armed aircraft were always kept locked). Imagine the panic when the co-pilot said that he did not have it and went on to remind the captain that he had been wearing it round his neck all day. In fact, the key was still hanging on the shower taps! In the meantime, the Vulcan’s engines were winding up without a crew onboard and, with well practised precision, the ground crew had started to remove the wheel chocks to allow the aircraft to taxy forward into position ready for take-off. Realising that all was not well, the crew chief frantically waved to his ground crew to replace the chocks and the prospect of an accident involving a fully armed Vulcan was avoided.

Whilst there were some small amusing incidents throughout this period of the Vulcan’s service, many will recall the impressive scrambles at airshows. This proved the viability of QRA by commonly launching 4 aircraft in less than 90 seconds.

I came across the story of how the Vulcan camouflage scheme originated, when I was on my first Vulcan tour as a co-pilot on IX

Sometime ago, while casually looking in my flying log book for entries involving XH558, a very similar Vulcan tail number jumped out at me. XH557,

Born in 1942, I obviously have few memories of WWII but one remains vivid. It is also the first distinct memory I have of any

As an 18-month-old baby Carolyn was fascinated by the Vulcan, so the story goes, her Dad was watching a programme about the iconic aircraft and