National Service Experiences with the Vulcan

Having recently joined the Guardian Squad I thought it might be an idea to put on paper, my contact with the Vulcan, during my RAF

On 2 April 1982, Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands. It was the beginning of a ten-week conflict that ended with the Argentines surrendering on 14 June and the islands returning back to British control.

Operation Black Buck was a series of seven ambitious long-distance ground-attack missions conducted by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Falklands War. The missions took place between 30 April and 12 June. It was the RAF’s most daring attack since Operation Chastise – the Dambusters raid in WWII.

Black Buck 1 is the most well-known story of the missions, being successful and being the first to achieve the longest-ranged bombing raid in history at that time. In this extract from Vulcan Boys by Tony Blackman, Vulcan XM597’s Nav Radar, David Castle, gives a completely unedited account of Black Buck 6, which took place on 3 June, and its diversion to Rio de Janeiro.

The following extract contains strong language.

David Castle records it all

The story of Vulcan XM607 and Black Buck 1 and its mission to bomb the runway at Port Stanley has been told and re-told many times before but very little is known of the three missions that were detailed to attack radar sites on the Falklands Islands to remove a serious threat to the UK Task Force that was, in May 1982, coming under increasing hostile air attack from Argentine fighter-bombers. This is the story of those three missions, Black Bucks 4, 5 and 6 told by the Nav Radar of the crew, David Castle.

This completely unedited account of the Black Buck sorties to the Falklands using the Shrike missiles and the diversion to Rio is absolutely spellbinding. We are very lucky that David Castle has taken the trouble to record this story down so that people will know what really happened.

“RIO IS A LONG WAY FROM HUDDERSFIELD”

“MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. This is a British four-jet approximately 500 miles east of Rio de Janeiro at Flight Level 430 with an in-flight emergency and very short of fuel. We require an immediate diversion to the nearest suitable airfield.”

“This is Brazil control; please say your call-sign, your country of departure and your destination.”

“This is Ascot 597, a British four-jet with 6 souls on board, critically short of fuel and with no cabin pressure. We request immediate assistance and permission to divert to the nearest suitable airfield.”

“Ascot 597, NEGATIVE. You do not have permission to enter Brazil airspace. Please state your country of departure and final destination.”

“Dave, I can’t move the escape hatch handle out of the locked position. There is no way we are going to be able to close this hatch and re-pressurise!”

“Try this Brian.”

I detached my aircrew knife from its sheath on my right thigh and handed it to Brian Gardner, the spare pilot of Vulcan XM597. Brian had been seconded to our crew to assist with the final and most critical AAR procedure after an epic twelve hours of our third and, as it turned out, our final Black Buck mission.

“Try and lever the handle out of its ‘detent’ position using my knife.”

“What?…What did you say? I can hardly hear you…say again…”

Brian and I endeavoured to communicate with each other over the maelstrom of cabin noise as we both straddled across the wide open escape hatch revealing a cobalt blue expanse of the South Atlantic ocean below us. With no cabin pressurisation, oxygen was being force-fed into our lungs under pressure from our oxygen regulators making us sound like characters from an episode of the Looney Tunes cartoon ‘Daffy Duck’. But this was no laughing matter. We both had parachutes on and I had my arms wrapped around Brian’s waste as he struggled with an obstinate escape hatch lever that was refusing to co-operate. How many times has a Vulcan escape hatch been opened at 43,000ft before, I wondered?

“MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY” continued Rod Trevaskus our AEO, this time on UHF 243.0.

“We are a British four-jet, 480 miles east of Rio at Flight Level 430, we are critically short of fuel and require immediate diversion assistance.”

“NEGATIVE, NEGATIVE, you must turn away. You do not have permission to enter Brazil airspace. You must identify yourself. What is your departure airfield, where……?”

“Brian, you need to force the handle out of the locked, detent position before the hatch will close again,” I interrupted.

“If we can re-pressurise we may be able to hear ourselves think,” I said with just a hint of irony.

By now the cabin temperature was starting to drop. It was minus 54 degrees outside and we were losing a lot of heat through the open hatch. My fingers were starting to tingle and I felt the on-set of potential frostbite. Adrenalin was pumping. I was really scared! ‘I must not release my grip on Brian’s waist’, I kept reminding myself. Neither of us can afford a slip or a stumble otherwise a long, very long parachute descent into the ocean below beckons.

“British four-jet, identify yourself and state your destination.” A second Brazilian controller with an American accent now appeared over the R/T. “British four-jet you must….”

“Oh for fuck sake Rod,” I screamed. “If he won’t be quiet tell him we’re from Huddersfield. Now Brian let’s have another go,,” I added in a rather less stressed tone!”

“Brazil control, this is Ascot 597 at Flight Level 430, inbound Rio International, from, er- Huddersfield,” proffered Rod to help the controller with his stubborn and persistent line of enquiry.

“Ascot 597, roger, standby ”

Brian gave me another nervous glance. We hadn’t been taught this procedure on the OCU and we certainly never practised it in the simulator. I could read Brian’s mind. ‘We don’t get paid enough through the X factor for this sort of thing,’ I am sure he was thinking as we eye-balled each other one more time.

“That shut them up,” said our nav plotter, Barry Smith. “They won’t have a clue where Huddersfield is.”

“There is only a light aircraft landing strip in Huddersfield and I doubt if it appears in any of their flight planning publications,” I spluttered over the intercom in an accent more reminiscent of Donald than Daffy Duck this time.

As a school boy from Huddersfield, my father would on many occasions take me to a vantage point on a hill overlooking a small light airfield on the outskirts of the town armed with a flask of coffee and an amateur VHF radio receiver. It was this introduction to the exciting world of aviation, along with regular visits in the summer to the Church Fenton and Finningley air shows that propelled me towards a career in the Royal Air Force. My teen-age ambition was always to fly Buccaneers. I never dreamed I would find myself one day as part of the crew of an air defence suppression sortie, somewhere over the South Atlantic – and in a Vulcan bomber at that!

There was no way the Brazilian military authorities would ever know that we were the crew of a Vulcan bomber based out of Ascension Island and returning from an attack against a surface-to-air missile fire control unit on the Falkland Islands; a mission that was now close to ending in total disaster with the crew considering abandoning its stricken bomber short of fuel off the coast of Brazil, thousands of miles away from its home base in Lincolnshire. But a mission that would eventually lead to the award of a Distinguished Flying Cross for the Captain of XM 597, Squadron Leader Neil McDougall. Or did the Brazilians really know who we were and where we had come from and, if so, what would be their reaction if we ever made land-fall and then Rio? If only we could close the escape hatch.

It was Easter 1982 and with my wife Chrissie and our new-born beautiful daughter, Elisa, we were taking a weekend break at the coastal resort of Filey in North Yorkshire. We were watching the BBC Nine O’clock News in our cosy B&B.

“Will the invasion of the Falkland’s Islands affect you, Dave?” Chrissie enquired.

“I doubt it very much; the islands must be over 7,000 miles away, not much we can do from here.”

We didn’t practise air-to-air refuelling or conventional bombing and the only weapon we trained to deliver was the WE-177 tactical nuclear bomb from low level against target sets east of the Urals.

“No, this is a job for the Royal Navy,” I added. “If only they still had the Ark Royal though with its complement of Buccaneers and Phantoms, their task would be much easier.”

Just a week before the invasion, I had sat on the duty officer’s desk of 50 Squadron at RAF Waddington and witnessed outside the systematic dismemberment of Vulcan airframes by a local scrap metal contractor. The Scampton squadrons had already gone and IX Squadron was about to disband in three weeks time, leaving the remnant crews of 44, 50 and 101 Squadrons until, they too, were expected to disband in August that year. I was approaching the end of my first tour as a navigator (radar) on 50 Squadron and was hoping for a posting to the Buccaneer, the aircraft I had dreamed of flying since I first witnessed a display of that awesome jet at RAF Finningley with my father in the sixties.

I had performed well as a nav radar and had gained the respect of my fellow crew members despite a shaky start on the OCU course at Scampton. Our crew had shone this year and had come third in the Strike Command ‘Double Top’ bombing competition, and I had worked extremely hard to be recognised as one of the squadron’s more capable navigators. But it still came as an enormous surprise to me to be selected, along with my crew, to be part of an Operation CORPORATE work-up programme in preparation for a deployment to Ascension Island. My feelings and emotions were a little confused. Only four crews had been selected. On the one hand, I was elated and proud to have been chosen ahead of many more experienced navigators on the squadron. And yet I felt apprehensive. We all did. Our first child had just been born and Chrissie was going to need me around over the next few months or so. Disappearing off to war did not really feature on her or my list of ‘things we must do on our first tour’.

The Cold War had presented a different kind of challenge to the military. This event had been rather unexpected and no contingency plan existed in the V-Force to cater for a scenario such as this. Nevertheless, this is why we were here – to respond to the unexpected and put our extensive training now into practice. The pace of life was just about to accelerate beyond anything I had experienced so far in my short Service career.

Our work-up programme began in earnest. None of the Waddington pilots had practised air-to-air refuelling in a Vulcan, that is with the exception of the Captain of our crew, Neil McDougal, a rather dour Scotsman with a dry sense of humour. All of a sudden, No 1 Group Air Staff Orders were relaxed and peacetime flying regulations went out the window. A different, more operational set of safety criteria was applied in our work-up. After two weeks intensive flying practice, a typical sortie would involve a climb to high level, a night transit navigating by periscopic sextant and the stars, including AAR from a Victor tanker, a let-down to low level over the Outer Hebrides. A low level ingress at 300ft AGL over the Inner Hebrides and west coast of Scotland using terrain following radar, the H2S radar and night vision goggles, culminating with the release of either twenty one 1,000lb live bombs at Garvie Range near Cape Wrath or seven inert bombs at Jurby Range off the Isle of Man. The Vulcan’s analogue and archaic Navigation and Bombing System, NBS, relied entirely on continuous radar fixing to keep it updated and the bomber on track. But Port Stanley airfield lay some 3,800 miles south of Ascension Island and the first radar fix would not be available until the coast of East Falkland Island came into radar line-of-sight. So we would have to perfect our night astro skills to give us a chance of being anywhere near our target when we descended to low level for the ingress under enemy radar cover. This would be an enormous challenge. I enjoyed night astro; I considered it an art as much as a science. I practised crewing-in to the aircraft wearing an eye patch so that one eye was already accustomed to darkness and that the dimmest star, the one that would provide the most reliable position line for a fix, could be recognised quickly. To get a good star shot required a calm, stable air mass to fly through and the activity would have to be de-conflicted with AAR. It also required four members of the crew to work in harmony with intense concentration for over ten minutes to obtain a reliable star fix. One hiccough in this sequence by any member of the crew could jeopardise the accuracy of the NBS and our ability to navigate successfully over such a vast distance. However, in practice we consistently achieved an accuracy of about four to five miles over a three to four hour sortie. As a crew, we were really proud of this achievement.

Fortunately, common sense prevailed and the four designated CORPORATE Vulcans were each fitted with a twin Inertial Navigation System, INS, robbed from VC-10s in storage in a hangar at RAF Brize Norton. On subsequent sorties our navigation accuracy was now in the order of three to four miles over an extended eight hours flying time. Good enough to slave the H2S towards its radar bombing offsets on the ingress to the target. Well that was the navigation sorted. But we would still need to make a successful RV with a Victor tanker, not once, not twice but four or five times outbound and then make a final RV with another tanker on our return to Ascension Island. None of us had previously practised with live or inert thousand pound bombs and, with the exception of Neil McDougal, not one pilot had any previous tanking experience. My own weapon effort planning calculations revealed that in order to achieve a seventy five per cent probability of cratering a 4,000ft by 150ft runway, using a navigation and bombing system with a CEP (Circular Error Probable) of 1,900ft, it would require up to seventeen sticks of twenty one 1,000lb bombs. As my grandfather would have said if he were still alive today, ‘you have as much chance of striking a match on wet tripe!’

No sooner had our crew, Neil McDougall, Chris Lackman the Co-Pilot, Barry Smith the nav plotter, Rod Trevaskus the AEO and myself got into its stride than our station commander, John Laycock, took Neil to one side to reveal that John Reeve’s crew had been selected for Black Buck 1. Our crew was to remain behind in the UK to conduct extra training for another type of mission; a mission that no one in the RAF had ever done for real before and one that only the Maritime Buccaneer Wing had any knowledge or experience of.

The Royal Navy Task Force commander had become increasingly concerned about the ability of the Argentinean search radars on the Falkland Islands to provide tactical direction to its Sky Hawks and Super Etendard fighter-bombers. Aircraft that were having a dramatic and damaging effect on our surface ships such as HMS Sheffield, Coventry and Ardent. There was intelligence that a mobile Westinghouse AN/TPS-43 was providing such a capability and Admiral Sandy Woodward was keen for it to be suppressed or even neutralised so as to remove the serious threat it posed to his Task Force.

“I need your crew to report to Ops Wing tomorrow morning Neil,” said Wing Commander Simon Baldwin, the boss of 44 Squadron.

You are to get a brief on the MARTEL Anti-Radiation Missile from Flight Lieutenant Phil Walters who has come up from Honington. You are going to convert to the SEAD(Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) role and you are going to have to learn it fast! In the meantime, here is an excerpt of the MARTEL check list from the Buccaneer Flight Reference Cards. Get your crew to inwardly ingest and learn the cockpit checks before tomorrow morning. 0800 hours prompt in Wing Weapons please.”

“They want us to do what?” exclaimed Rod Trevaskus!

“Strap a 1,200 pound MARTEL missile onto a Skybolt pylon, fly four thousand miles to the Falklands, loiter for thirty minutes in the overhead of Stanley, be shot at, and then attempt to lock up and destroy a mobile TPS-43 radar without knowing its precise location. You’re having a laugh!”

Again, this was no laughing matter. This was a serious proposition and Phil Walters briefed us enthusiastically about the missile’s capabilities, strengths and foibles. The big problem with the MARTEL was that weapon effort planning revealed only a sixty per cent probability of kill, Pk, for a single shot missile launch, and with intelligence reporting that the TPS-43 changed its location each day, there could be a high probability of failure, let alone the risk of collateral damage on the outskirts of Stanley town from its powerful 350 pound blast fragmentation warhead.

I recall being summoned to the squadron hangar on a Sunday morning to assist with cockpit and power-on checks to a MARTEL ARM hanging from some Heath-Robinson pylon assembly, and by the Wednesday of that same week we had launched the missile live at Aberporth Range – but what a disaster that nearly turned into. MARTEL had a number of safety breaks and so, naturally, we disabled the warhead and took the extra precaution of disabling its sustainer motor. Only the booster motor would fire so we could demonstrate that the missile could be launched from a Vulcan and that the radar homing head would guide towards a target radar emitter. The plan was for the missile to fall short of the radar by about 2 miles or so into the sea. However, when the booster motor ran out of fuel the missile continued to porpoise like a laser guided bomb towards its target and caused sufficient consternation and panic in the range hut for the Range Safety Officer to shut the radar down and evacuate his position! The missile fell short by only a few hundred metres and impacted on the beach! Phew!

“Well that worked chaps,” I said to the crew in our debrief. “But what about its Pk? 0.6 isn’t very good, despite that impressive performance at Aberporth.”

“And what about the target’s proximity to Stanley,” Barry reminded us. Perhaps MARTEL was going to be too risky.

The following day we were introduced to Flight Lieutenant ’Herm’ Harper from the Aeroplane and Armaments Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down. The US Government had secretly agreed to supply the MOD with a batch of AGM-45 Shrike missiles that had been used to great effect by F-4s and A-6s during the Vietnam War, and ‘Herm’ had some knowledge and insight of the missile’s capability from his trials work both in the US and at Boscombe Down.

“The good news,” Herm opened with, “Is that Shrike can achieve a Pk of up to 0.9.”

“And the bad news?” I asked.

“Well you would need to launch two in quick succession and you will need to get as close as seven miles to the target.”

Group Captain Laycock took Rod Trevaskus and me to one side to see what we thought and whether we could come up with an improvised tactic. How would we locate the TPS-43? Would we be able to achieve a firing solution? What were our chances? John Laycock needed to know and needed an answer quickly.

“Well, if we were able to obtain an intercept bearing on the Radar Warning Receiver (RWR) from the TPS-43,” suggested Rod, “And then from Dave’s interpretation of the H2S radar we were to manoeuvre the aircraft so as to obtain another cross-cutting bearing, we could in theory obtain a two position-line fix on the TPS-43.”

“I could then drop my radar markers over this location so as to ascertain our range from the TPS-43,” I concluded.

“A bit of a long-shot,” suggested Rod

but we both believed with a bit of further refinement we could get it to work. On the planning table in front of us, Herm unfolded an A3 sized sheet of graph paper depicting the missile’s engagement parameters in a series of concentric circles and parabolic curves.

“Look at this footprint,” said Herm. “If you launch from precisely 6.9 miles in a ten degree dive, whilst bore-sighted against the radar head you can achieve a Pk of 0.7. If you were able to ripple fire two Shrikes in quick succession in a twenty degree dive, that figure rises to 0.9. However, you can see that if you over-run by just 0.1 mile, the Pk drops off a cliff to as low as 0.2 and to zero by 6 miles. How confident are you of your radar skills Dave because you will have to determine the launch point; the INS will not be accurate enough.”

“It all depends on whether the radar is mobile or not and how certain of its location we can be. I can use radar offsets to help me fix its geographic position but the radar will still need to radiate for the missile to guide and home in. OK, I may be able to determine a range from the H2S radar but Rod will still need to give the pilots a steer so as to bore-sight the missile before launch and give the Shrike’s homing head a good chance of seeing the emitter within its narrow field of view. Barry, you will need to call down the range-to-go from the output of my radar markers, and the handling pilot, Neil or Chris, will need to make sure we have achieved at least a ten degree dive before the launch point.”

“I’m going to have to ‘bunt’ the aircraft to achieve a dive like that, a tip-in manoeuvre is out of the question,” said Neil.

“Any dive is better than a level release,” replied Herm. “But it’s the release range that is absolutely critical to achieve a kill. And of course, this is all predicated on the assumption that the Argentinians will switch their radar on. Good luck chaps, you’re going to need it!”

John Laycock was impressed with our enthusiasm and was content to recommend our tactic to Group for their authorisation.

There was no time for in-flight trials of the Shrike missile, let alone a live firing at Aberporth this time. On 10th May our crew was alerted and told we were to be collected at 0500 hours and taken by road transport to RAF Brize Norton where we would embark on a VC-10 for Ascension Island. There was no spare ramp space on Wideawake airfield for another Vulcan, so the Shrike missiles would be airlifted there also. Now the following tale may have been told many times before and some would say it is anecdotal if not apocryphal. Well I can vouch for its authenticity because I was there as a witness. The VC-10 had been re-rolled for freight with just a half dozen seats remaining in its tail section. Amongst all the ammunition crates and supplies were two open racks of Sidewinder AIM-9L air-to-air missiles destined for the Task Force and eventually the Sea Harriers embarked on HMS Invincible and Hermes. Each AIM-9L had had its safety pins removed and when I enquired of the corporal Air Load Master where on earth they were she pointed to a card board box on the cabin floor where she had gathered them all.

She explained, “The red flags on the pins said ‘REMOVE BEFORE FLIGHT’, so I pulled them out and kept them in this box for safe keeping.”

“What the!……I was suddenly rendered speechless.

But fortunately not Neil who bellowed at her to put the pins back in before we got airborne! I was not yet a QWI (Qualified Weapons Instructor) in 1982 but even as a Vulcan nav radar I knew how important the pins were to the safety and reliability of those precious missiles.

“What the hell are you lot doing here?” demanded Squadron Leader Bill Sherlock as we tried to disembark the VC-10 at Wideawake airfield following a laborious eight hour flight from Brize.

“You tell us Bill,” pleaded Neil as the rest of the crew gathered its kit and was about to disappear across the tarmac for an ice cold lager in the Volcano Club.

“I’m sorry Neil but the Base Commander, Group Captain Jeremy Price does not want you here. He has told me to send you straight back to Brize. There is no accommodation for you all and your mission has been put on hold as a result.”

“What – you must be joking.” He wasn’t!

“If you don’t allow us just one beer before this jet is refuelled and turned round you are going to have a mutinous crew on your hands Bill,” protested Neil.

A six-pack of South African Castle lager and thirty minutes later we were airborne once again, this time en route back to RAF Brize Norton, only nine hours after we had departed from that same airfield.

We were to return, nevertheless, to Wideawake airfield under our own steam in Vulcan XM 597 on the 26th May, this time equipped with two AGM-45 Shrike missiles suspended from two Heath-Robinson, makeshift pylon assemblies under each wing. Whilst we had trialled the MARTEL missile and achieved a successful live firing at Aberporth, we did not have the same luxury or opportunity for Shrike. The only test we were able to make was to check the homing head sensitivity against RAF St Mawgan’s ATC radar as we coasted out over the Cornish peninsula. But would it fly off the rails when Rod Trevaskus pressed the firing button in anger, and would it guide? Only time would tell.

Later on in my career with 12 Squadron in the Maritime Strike Attack role, I experienced many an encounter with Soviet intelligence gathering ships masquerading as fishing trawlers off the Scottish coast. But my first introduction to this Soviet capability was at Ascension Island where one such vessel, decked out with a sophisticated array of aerials and sensors, was positioned some ten miles to the south of the island. It was assumed that the trawler was just gathering routine intelligence but in reality it may well have been alerting the Argentineans to our formation’s launch out of Wideawake. This only came to my attention when I recently read a report posted on an internet forum by a former member of Grupo de Artilleria Antiaerea (GAA) 601 that revealed the unit had been receiving tip-offs of the take- off times for Black Bucks 4, 5 and 6, and could therefore calculate our ETA over the Falkland Islands.

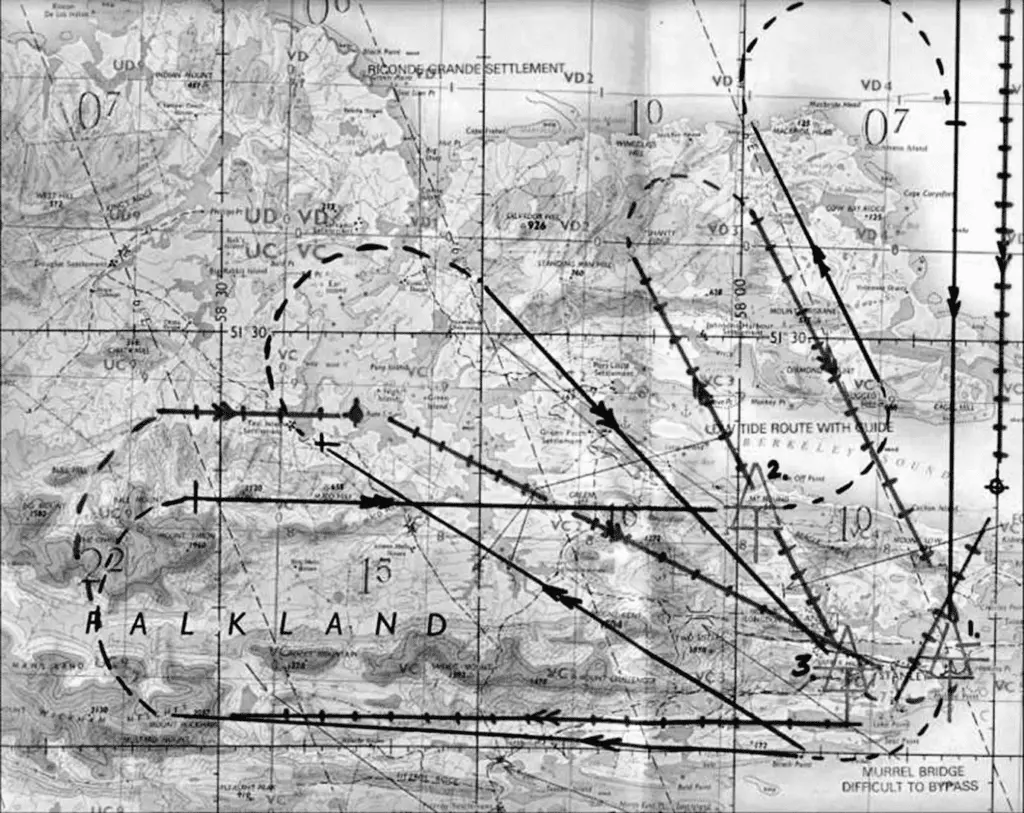

Black Buck 4 launched at midnight on the 28th May with the task of neutralising the Westinghouse TPS-43 radar, located ‘somewhere’ on East Falkland. This was not a SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) mission where we would be required to ‘suppress’ the radar site whilst another formation conducted simultaneous attacks on other designated targets. There was no coordinated Harrier GR3 attack planned for that morning and so this would be more a DEAD than SEAD mission (destruction rather than suppression). Intelligence reports indicated that the TPS-43 was being constantly rotated through three locations: one on Mount Round, one on Sapper Hill and a third close to Stanley on the outskirts of the airfield. Our aim was to locate the TPS-43, fix its position, get a lock on and ripple fire two Shrikes in quick succession in a twenty degree dive from a sanctuary height of 12,000ft and at the all-important range of 6.9 miles. As both Skybolt pylon positions had been taken up by the Shrike missiles we would not be able to carry the Westinghouse ALQ- 101-10 ECM pod afforded to both Black Bucks 1 and 2 for self-protection in order to jam any fire control radar that threatened us. Intelligence told us to expect Roland surface-to-air missiles and Oerlikon 35 mm guns capable of engaging targets up to 10,000ft with their Skyguard fire control radar. But this was not a covert mission; we would not have the element of surprise and we were not going to jam their radars. We would have to announce our presence, remain in the overhead in a search pattern, locate and identify the sites and entice the TPS-43 into illuminating us. We should be safe from the triple A and Roland as long as we remained above 10,000ft.

Just before midnight, pre-flight systems checks were completed, including a short burst of H2S radar, away from the Soviet trawler, to confirm its serviceability. An unserviceable H2S was clearly a no-go item. Take-off in total R/T silence was followed by an uneventful climb to 33 000ft, that is until I continued with my NBS system checks. To my horror I found that I had no radar markers. Without a range and bearing marker there was no way I could mark and locate with accuracy the TPS-43 radar. Or was there? I suddenly recalled my OCU training and the tips Squadron Leader John Williams had given me at an early stage of my squadron work-up programme. Now I was going to have to earn my flying pay and improvise more in order to generate some radar markers to enable me to call an accurate release point for our Shrike attack. The only way of generating alternative markers was by drawing out some long-winded trigonometrical equations and by winding the calculated coordinates, in yards, onto the radar offset potentiometers. I didn’t have a slide rule let alone a pocket calculator and so I was going to have to do this by long hand.

“What’s your problem Radar?” enquired Neil our Captain in his usual Scottish dulcet tone.

I explained our situation. It was not ideal but I offered him a crumb of comfort.

“We will have to abort the mission if you cannot guarantee a satisfactory targeting solution,” said Neil. How long do you need before I call an abort?”

“Give me twenty minutes and I will let you know if it is feasible or not,” I said enthusiastically.

Well I didn’t need to apply my physics degree to this task but I now understand why the minimum requirement from the Biggin Hill aircrew selection process was for at least five O levels, one of which had to be Maths.

After about twenty minutes or so I piped up:

“Happy. I’ve calculated the offsets for all three of the possible locations at Sapper Hill, Mount Round and Port Stanley, and Barry has checked my figures. I am confident we can still do this; there is no need to abort Black Buck 4.”

Four hours into the sortie, just as we prepared for the final fuel transfer, our accompanying Victor tanker broke radio silence to announce that his Hose Drum Unit was unserviceable. He would not be able to transfer any fuel to us and therefore the mission would have to be aborted after all. The sense of disappointment and deflation was overwhelming for us all. We were 60 minutes from our descent position and only 700 miles from the Falklands. All that hard work getting here, all the preparation and planning, all the time spent developing an improvised tactic to defeat the Argentineans’ search radar capability, all my impromptu trigonometry, all of it would now go to waste. The DNCO (Duty not carried out) entry in the Form 700 and authorisation sheets following our return said it all!

Our disappointment was short-lived. The following evening on the 30th May we launched yet again at midnight, in darkness and in total R/T silence with a formation of 10 Victors. Chris Lackman our Co-Pilot popped his two Temazepam pills to help him sleep and he snuggled down over the escape hatch in an air ventilated suit and sleeping bag for warmth. ‘Snuggle’ isn’t quite the right word as the escape hatch door was not the most inviting or comforting place in the cockpit to grab a nap but there was no other space available; the visual bomb-aimer’s position in the nose section under the pilot’s ejector seats had been taken up by a crate on which were mounted the Carrousel INS gyros and integrators. Meanwhile Brian Gardner, the third pilot who was seconded to the crew to assist with air-to-air refuelling, took his place in the right hand seat. The refuelling brackets passed by without serious incident this time. Thirty minutes prior to our descent to low level I clambered down over the escape hatch to awaken our Co-Pilot Chris. Chris was already wide awake. The tablets hadn’t worked. Or had it been adrenalin that had kept him alert with eyes wide open for the past seven hours. Brian and Chris exchanged positions again for the descent. Chris had to switch on quickly; we were just about to enter a dragon’s den.

“Top of decent checks please,” requested Neil.

And down we went, some 240 miles north of East Falkland.

“Flight Level 300,” I called passing 30 000ft in a cruise descent. “Flight Level 200,…100, nine zero, 80, 50. Set the regional QNH……one thousand feet. TFR checks!”

“500 feet, 300, 200 steady.”

I cross-checked with our radio altimeter. Bang on the money. We accelerated to 300 knots for the ingress.

“This is it guys!”

The plan was to penetrate under the radar horizon and then carry out a steep climb to 12 000ft with about fifty nautical miles to run. Has our navigation been accurate enough? Will the H2S radar work when I switch on the transmitter? Will my markers work? Will I be able to identify the radar offsets? Will we be safe at 12 000ft or is there a Roland missile system in the vicinity? So many questions on my mind. So many uncertainties. Too many things to go wrong!

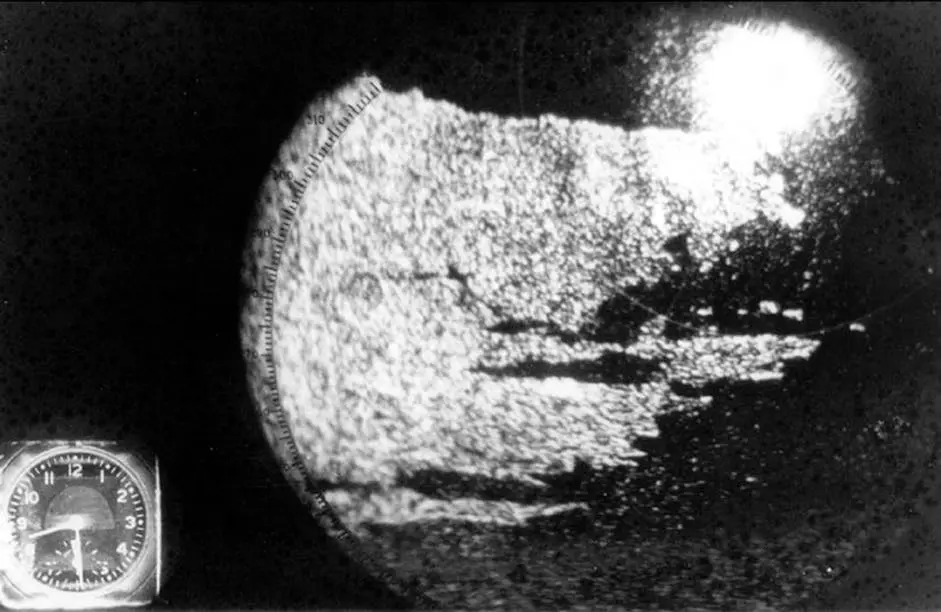

With fifty miles to run on the Carousel INS, we initiated our climb to height. This is the moment of truth, I thought. Tilt set correctly, sector scan selected. I switched on the H2S for a couple of sweeps and, lo and behold, Cape Pembroke was only three miles off my radar markers. Fucking brilliant, I thought. Now, let’s update the NBS. But there was silence over the R/T and intercom. No bleeps, no burps. No search radar, no fire control radar, absolutely nothing!

And then, just as we levelled out, there it was in the E-H band of the spectrum, the TPS- 43 had burst into full voice like a skylark in spring. We set off on our improvised race track to the west above the possible locations of our adversary radar in an attempt to fix its position. We then opened out to the north of Stanley to get a cross-cut bearing and turned 180° south to fly a menacing run towards the airfield. Perhaps they will think we are a bomber and will try to engage us. And then, as if they had just heard our protestations, suddenly there was a ‘spike’ on the RWR about 20 degrees left of the nose but in the I-band of the radar spectrum this time.

“Think that’s a Skyguard,” exclaimed Rod enthusiastically over the intercom.

There it was again, this time for 5 seconds or so, a very distinctive rattling sound.

“They’re not daft,” added Rod.

From our pattern of triangulation and by using a process of elimination, some mental arithmetic and a big dose of intuition, we deduced the location of the TPS-43 and I selected my radar offsets. Having triangulated its location I could now refine my radar markers and provide the pilots with a steer to their flight director, and with range information for Barry and Rod. Neil pulled 597 into a tight turn back on to a reciprocal heading. We opened out to the north once again. We had sufficient fuel for about two more patterns and two more attempts to engage the radar. Surely they don’t know we are ARM equipped. Why won’t they keep their radar switched on? If they thought we were a bomber they would try and engage us surely. They won’t want another stick of twenty-one thousand pound bombs raining down on their heads, I thought.

“There it is again,” exclaimed Rod with excitement as we turned inbound; an E-band spike appeared on the RWR once again. “Come left twenty – roll out. That’s a good steer. What’s our range Dave?

“Standby….zero demand, HRS to central,”

I called to the pilots as I refined my radar mark to deduce the range to go. Chris had now re-calculated that we only had fuel for this one attempt. We had to get it right. We had to nail the parameters. Suddenly the TPS-43 went silent again.

“Range Nav?”

“Eighteen miles to run. Fifteen, fourteen….,” Barry replied. A burst of E band energy appeared again on the RWR.

“Come right five degrees, roll out, that’s it, steady.” Rod’s voice was now reaching a crescendo.

Neil pushed on the stick and bunted 597 into a dive.

“Ten miles,” cried Barry. “Nine, eight, standby…..FIRE!” Barry hit the stopwatch almost immediately.

Rod pushed the fire button, waited for a jolt, re-selected the pylon and pressed it once again. A second vibration indicated that both missiles had fired off the rails. This was confirmed to us in no uncertain terms when the cabin was suddenly filled with the smell of cordite. What an enticing aroma, I thought. Suddenly the sky was lit up like Guy Fawkes Night as the Super Oerlikon guns opened fire on us with the assistance of their Skyguard fire control radar. The smell of cordite now evoked a different, rather less comforting sensation. The RWR was ablaze and the TPS-43 was in full voice.

“Ten seconds,” called Barry. “Fifteen. That’s twenty. Twenty-five, six, seven, eight, nine, thirty seconds.”

Then silence. The RWR went totally quiet.

“Yes. It’s down. We’ve hit it. We must have, surely! I’ll do a BIT (Built-in Test) check just to make sure the RWR is still serviceable,” said Rod. It was.

The predicted time of flight of the missile based on the release parameters was thirty seconds. It would have to be an enormous coincidence for the GAA 601 crew to switch off their radar at this precise moment.

“Right, let’s get the hell out of here.”

Neil pushed the throttles wide open and pulled 597 into a steep climbing turn from 10,000ft. Full power was applied. The sound and vibration from the four Rolls Royce Olympus engines had never sounded so comforting and re-assuring. No one was going to catch us now, not even a Mirage if there had been one in the vicinity; we were safe – for a while at least.

We debated at length the chances of our success on the long transit back to Ascension. Was it a coincidence that the TPS-43 operator had switched off his radar at 30 seconds on the stopwatch? Without instant Battle Damage Assessment, BDA, we would not know with any certainty until long after we had landed, and possibly not even then.

Then it dawned on us. We still had to make our final RV with a Victor from Wideawake and successfully tank from him otherwise our perceived success could soon become a failure.

The final RV was made with our lone tanker, courtesy of a radar operator in a supporting Nimrod who helped us to locate and converge on each other without too much of a fuss. Fuel was transferred without a glitch and we flew into aviation history having completed the longest combat mission in the history of air warfare; precisely sixteen hours – five minutes longer than Vulcan 607 and Black Buck 1.

We celebrated with a few more Castle lagers back in our accommodation at Two Boats village but our celebrations were short-lived. Intelligence had reported the following day that the TPS-43 had indeed been damaged by the Shrike’s 150lb blast fragmentation warhead impacting a few metres away from the radar head but a spare wave-guide assembly had been flown in that same day from the mainland and it was back up and running once more. So we would have to go back and do it all over again.

On Black Buck 5 we had spent around thirty minutes in the overhead of East Falkland allowing me time to interrogate the same radar offsets that had been used for Black Bucks 1 and 2. Radar significant points such as a coastal feature, TV mast or corner of a building were used to engage a target that did not show up well on radar. The coordinates of these offset points were calculated in relation to the impact point required for the bomb load. An internal offset was preferred to an external offset due to its closer proximity to the target, thereby minimising the radar aiming errors. On passing over the airfield I had identified the Stanley ATC tower as the internal offset used for Black Buck 1 with a high degree of confidence and so for Black Buck 6, I pleaded with the ops staff and mission planners at Ascension Island to allow us to carry a bomb load in the bomb bay in addition to our Shrike payload on the wing pylons. I was utterly convinced of my ability to deliver a bomb and crater the runway and felt we could do it with only a stick of seven; there was insufficient space in the bomb bay for twenty one thousand pounders with a bomb bay fuel tank fitted and our loiter plan would benefit from the fitment of a second tank. My request was rejected but I suppose common sense had prevailed again. The priority now was to neutralise the TPS-43 and not crater the runway.

Our down-time lasted a little longer this time, which included an extra day’s relaxation and time to modify the Shrike tactic based on our experience and lessons learnt from the day before. We had of course detected a Skyguard fire control radar operating in I-band of the radar spectrum and so elected to take a total of four Shrike missiles on Black Buck 6; two optimised against the TPS-43, our primary target, and two optimised against Skyguard should they attempt to engage us again.

That evening I played the best game of snooker ever in my life in the Exiles Club in Georgetown. Never before in all my misspent youth in the snooker hall at Liverpool University, and never again since in an Officers Mess, have I ever made a break of 67. I was on fire. Perhaps all the adrenalin flowing in my body had heightened my senses to enable me to pot so many blues, pinks and blacks with such consistency. Then again, perhaps it was just a big dose of luck. I hoped the good fortune would remain with me and our crew just a little longer. We were going to need it over the next 48 hours.

On the evening of 2nd June a small crew bus arrived to collect us from our accommodation at Two Boats village. We asked the driver to detour via the NAAFI in Georgetown as we wanted to supplement our in-flight rations with extra cans of Coke and fruit juice for our next mission. Much to our chagrin, the NAAFI store manager refused to serve us.

“These supplies are for Georgetown residents,” the manager said. “You guys are depleting our stocks, go away.”

All we wanted were a few cans and choccy bars as the detachment supply of in-flight rations was inadequate for a sixteen hour sortie. Our pleas fell on deaf ears and so for the next ten years I boycotted all NAAFI shops in the UK. They clearly didn’t need my business and I didn’t want theirs.

Crew-in, start-up, taxi and take-off at Wideawake was now a familiar routine to us. Power on and systems checks were completed with no-go items fully functioning, particularly the Shrike cockpit indicator, H2S radar, RWR and Carousel INS. We launched in total R/T silence again with ten Victors at thirty second intervals. In daylight it would have been a very impressive spectacle. At night it was just an incessant wall of noise!

Black Buck 6 followed an almost identical profile to that of Black Buck 5. There was only one way to ingress; we had insufficient fuel to push further south and approach from a different cardinal point. At fifty miles we pulled up from our run in height of 200ft above mean sea level and initiated a climb to 12,000ft where we settled down into another racetrack pattern to try and entice the TPS-43 into action.

Again nothing! Not a single bleep or single burp on the RWR. As we predicted, they suspected our motives and their radars stayed stubbornly silent. They had learnt a valuable lesson from our previous encounter and were, sensibly, leaving their radar in standby mode. Had that Soviet trawler tipped them off? Are they unaware of our presence? I can’t believe that, I thought.

Suppression of enemy air defences or SEAD is a mission or capability that most modern day air forces possess and practise. The USAF first employed SEAD to good effect in Vietnam with Shrike and in Gulf War 1 with HARM. The principle is to suppress or deny the enemy his use of surveillance and fire control radars so as to facilitate other capabilities carrying out attack missions such as air interdiction or an airfield attack. For a SEAD mission to be successful, all it had to do was ensure the enemy’s radar stayed silent. The arrival of Black Buck 6 overhead Port Stanley airfield was timed to coincide with an airfield attack by RAF Harriers launched from HMS Hermes.

The aim of the Harrier’s attack that morning was not to crater the runway but to destroy soft targets such as static Puccara aircraft and airfield buildings. To crater a runway required a high explosive bomb with a forged steel casing to be dropped from sufficient a height to impact it with a terminal velocity capable of penetrating concrete. As the minimum stick spacing between two bombs dropped by a Vulcan was equivalent to the width of Port Stanley runway, the optimum attack angle would need to be between thirty and forty degrees to the runway direction to have any chance of scoring a hit, otherwise two adjacent bombs in a stick could straddle the runway without impacting it.

One of my most abiding memories from Operation CORPORATE was attending a brief in the main briefing room at Waddington during the final stage of our work-up programme in April. A senior air ranking officer had visited to wish us good luck prior to our deployment to Ascension. At the close of the brief this senior officer rose to his feet, coughed and then posed a question to the crews gathered in front of him:

“I have just one final query gentlemen. Can you just explain to me why you haven’t chosen to fly at night down the centre-line of the runway at low level so as to drop a neat pattern of twenty one thousand pound bombs down its full length to crater it and put it out of use? After all, we have sourced some NVGs (Night Vision Goggles) for you.”

Our station commander, Group Captain John Laycock took him to one side and politely explained the principle to him once again. The rest of us just looked at each other in total amazement and shock.

The reason for our attack profile on Black Buck 6 was to simulate yet another bombing mission in the hope that the TPS-43 would switch on and illuminate us. Well the concurrent GR3 attack probably confused the enemy rather than clarified the situation for them. But still the TPS-43 refused to play.

“Right, we are going to have to go completely naked and bare all,” said Rod. “Keep your radar on Dave, let’s see if we can entice them to come out and play.”

“Come on guys, switch on. Here we are again, come and get us! You must be able to hear these thundering Olympus 301 engines, even from our perch at 12 000ft!”

Suddenly we heard a bleep on our headsets.

“Missed that” said Rod, “but it sounded like I-band. There it is again, I-band, definitely.”

We continued with our game of ‘cat and mouse’ for almost another twenty minutes attempting to triangulate the position of the TPS-43 but the Argentineans were playing hard to get.

Chris Lackman interrupted our conversation.

“Hey guys, we have enough fuel for one more circuit before we need to bug out.”

We were becoming increasingly frustrated when Neil announced

“I’ll be beggared if I have come four thousand miles just to listen to electronic bleeps and burps on that RWR.

Flight Lieutenant Herm Harper from Boscombe Down had informed us that, as a last resort if the radar did not emit, we could always launch the missile ballistically in a dive but the chances of scoring a hit would be extremely slim. Again, that assumed we knew the precise location of the mobile radar beforehand.

“Dave, can you ascertain the location of that radar?” enquired Rod.

“From what I can deduce, it looks like a Skyguard emitter close to the airfield. I’ve got my markers over its possible location so we could prosecute an attack if we have enough fuel.”

“Ten minutes to Bingo,” Chris interrupted.

“OK, proposed Rod. “Let’s give it a go. The airfield attack is probably complete. They may feel they are now safe. Let’s assume it’s on the airfield then.”

Neil tipped 597 onto its wing-tip and opened out to the north one last time. We knew we only had one shot at this. But we needed the enemy radar to emit.

“Twenty five miles to run,” said Barry.

I was confident of my radar mark.

“Come on, come on, switch on, switch on, I pleaded.” Nothing!

“Twenty miles, nothing on the RWR,” confirmed Rod. “Captain, we are going to have to assume the Skyguard is on the airfield and launch one of the Shrikes in its ballistic mode,” he added. “Perhaps if they see an explosion on the airfield they might decide to switch on the TPS-43.”

“Right, we are going down,” said Neil, as he bunted 597 into a steep dive from 15 nautical miles.

“Ten thousand feet exclaimed Barry, nine thousand!”

Suddenly the Shrike cockpit panel meter detected a faint signal.

“Come left ten,” screamed Rod. “Roll out now.”

The Shrike had the Skyguard in its sights and its talons were now unfurled.

“Ten miles,” cried Barry.

“Nine, eight, standby,

FIRE!!

Rod pushed the fire button and made the switch selection for the second Shrike. The second missile juddered loose and filled the cockpit with the enticing smell of cordite again.

I pulled my head out of the radar screen and glanced across at the radio altimeter.

“CHECK HEIGHT, SEVEN THOUSAND FEET.”

The RWR lit up like a Christmas tree. All hell had broken loose over the airfield and we bottomed out at six thousand feet amidst a salvo of triple A from the Super Oerlikon guns. The sky pulsed with shards of light in the clouds all around us as Neil applied full power and recovered us to our sanctuary height of twelve thousand feet. Barry counted down the time on the stopwatch as he had done on Black Buck 5. Twenty seconds had elapsed and the Skyguard was still active. And then, as if on cue after 30 seconds, total silence.

Twenty years after this event, Group Captain John Laycock forwarded to me an article from a South American publication that provided a historical account of our attacks from the perspective of Grupo de Artilleria Antiaerea 601 where the unit revealed that the TPS-43 had been temporarily damaged on Black Buck 5, and a Skyguard radar had been completely destroyed with the loss of four operators and a fifth injured on Black Buck 6. We had been fortunate on Black Buck 6. We believe that the Skyguard radar had probably been in standby mode but that its frequency modulators were probably still running and that is what the hyper-sensitive Shrike homing head had detected. As Tony Jacklin the golfer once said: ‘The harder I practise, the luckier I seem to get!’ Up until this revelation by GAA 601, there was not one senior officer in Strike Command who was prepared to recognise or acknowledge the operational success of these two missions.

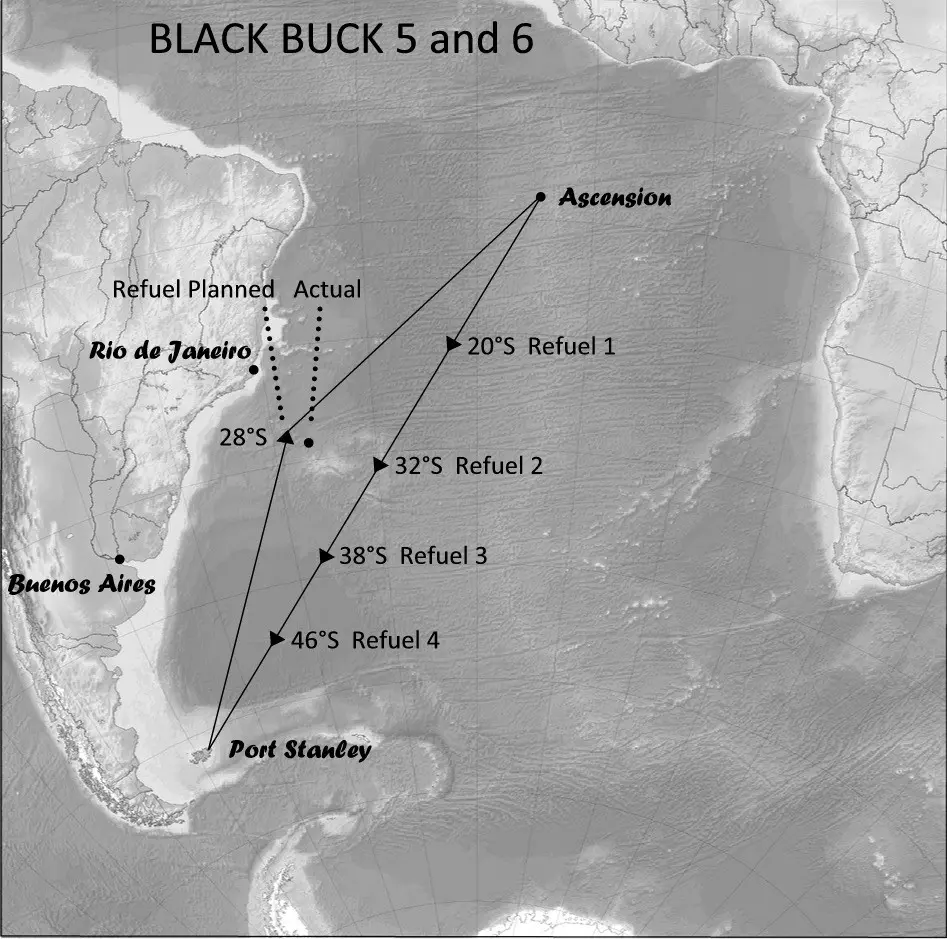

Our egress from the target area over East Falkland was uneventful apart from the odd spike on the RWR that had us thinking about the possibility of a Mirage Combat Air Patrol in the area. But we had a True Air Speed of 480 knots or eight miles per minute and so any adversary would probably need to go supersonic to catch us and that would almost certainly use up most of his fuel reserves. Again, we debated at length the chances of the Skyguard switching off after thirty seconds at the precise moment the missile was expected to impact. As we approached our RV with the Victor for our final but most important refuel point, Chris and Brian exchanged positions once more. The whole rationale for bringing Brian along was for him to relieve Neil McDougall after thirteen hours in the air and assume responsibility for the final refuelling bracket. Controversially though, Neil elected to conduct the final AAR procedure himself rather than relinquish the task to the more refreshed and rested Brian Gardner.

The Victor turned up on cue, assisted by a Nimrod for the RV, and Neil’s attempt to connect with the basket on the first prod was rather abject. It was clear to us all that he was really fatigued but that was unsurprising. He began like a bull in a china shop.

“Let me have a go,” suggested Chris as Brian was still not allowed into the right-hand seat.

“No I’m fine,” answered Neil but his second, third, fourth and fifth attempts were no better. On the sixth prod, disaster struck.

“Shit,” muttered Neil with rather un-subtle understatement.

With single-minded determination and stubbornness, his final attempt resulted in the probe penetrating the basket, damaging its spokes and sending splinters of aluminium down the engine intakes, damaging the inlet guide vanes of numbers 2 and 3 engines, and leaving the tip of the probe embedded in the basket!

The stark realisation of our predicament suddenly dawned on me. Without an uplift of fuel there was no way we would make Ascension Island. We were doomed. We had no diversions to fly to. Our rendezvous with the tanker had been further East than planned so that the Brazilian coast was almost 800 miles away and we only had sufficient fuel for about an hour and a half’s endurance or 700 miles range. Our brief from the ops team back on Ascension was that if such an event occurred we should abandon aircraft and take to our dinghies. The thought of spending the remainder of the conflict bobbing about in a single seat dinghy, miles from anywhere, waiting for some super tanker on the off chance to stumble across me did not really appeal!

Chris Lackman quickly totted up the fuel tanks and with only 13 500lbs remaining declared that we would not make land-fall. The only charts Barry and I had, with the exception of our targeting material and a quarter million scale map of the Falklands, was a 5 million scale chart that portrayed the whole of the South American coast from Panama in the north to Punta Arenas in Chile to the south, and the whole of the west coast of Africa from the Southern Cape to Morocco. We had no TAPs (Terminal Approach Chart), FLIPs (Flight Information Publication) or diversion publications. All of those had been commandeered by the Victor and Nimrod crews on Ascension leaving us with a single photo-copied table of radio frequencies for Brazilian airspace. Yet it was they who were supposed to be supporting us not us them.

“Where is the nearest airfield navs?” enquired Neil.

“It’s going to be Rio de Janeiro,” Barry replied.

I agreed and did a quick ready-reckon calculation to confirm our perilous fuel state.

“Bollocks,” was one of the more printable exclamations from the combined rear crew.

Neil eased back on the stick and commenced a cruise climb from 33,000ft to Flight Level 430.

“That should help eke out a few hundred more pounds of fuel,” said Barry. “But will it be enough to make Rio?”

Unknown to us at this juncture XM 597 had developed a fuel leak from the galley between the wing tanks and bomb bay tank. Every attempt by Chris to re-balance the fuel tanks with the cross-feed cock resulted in us losing more fuel from a fractured fuel pipe. This was just not our day.

I placed my radar markers over the part of the Brazilian coastline that approximated to Rio de Janeiro and provided a rough steer through the flight director to the auto pilot. The coast was still over 400 miles away. A further more detailed fuel check from Chris provided us with a little more optimism but it would still result in us having to bale out fifty to sixty miles short of Rio as the engines flamed out one by one.

“Hang on,” exclaimed Rod. “If we do make it, what are we going to say about where we have come from and what we have been doing?”

“And what about the two remaining Shrikes?” added Barry. “There is no way we could claim to have been on a radar reconnaissance sortie with two ARM missiles slung under the wing.”

“Best we jettison them,” said Neil.

Rod reminded Neil that we had no safe jettison capability and that we would need to live fire the missiles off the rails.

“Nav Radar, search ahead and check the sea for any surface vessels. We can’t afford another major incident today.”

Many fishing boats are equipped with radar for navigation and these often transmit in the I-band of the radar spectrum. As the Shrikes had to be launched with the warhead enabled, the last thing we needed was for one or both to guide and home in on a Brazilian trawler. That would have made us even less welcome in Rio if we were to make it to the bar that evening.

I switched on the H2S radar and to my horror there was what appeared to be a fishing fleet forty to fifty miles ahead of us on a westerly bearing.

“We will need to come left by at least sixty degrees before we launch the Shrikes,” I advised.

So for good measure Neil brought 597 hard left through ninety degrees onto a southerly heading.

“OK, AEO,” I said to Rod. “You are clear to live jettison,” I added as I played with the tilt and gain of the radar.

“Firing in three, two, one….” That’s one away. Firing the second in three, two one……This time there was no judder or vibration. “I think we have a hang-up,” called Rod.

He tried again and a third time, but either the firing pulse had failed or there was a problem with the launcher or missile, or both. Neil brought the aircraft back on to a westerly heading before we exacerbated our fuel predicament any further.

“We have another problem,” suggested Barry. “What about all our planning material, charts, maps, H2S R88 radar film, crypto and code-words? If we do make Brazil, there is a potential intelligence windfall for their authorities here.”

There was only one way of disposing all of the sensitive and classified material and that was by opening the escape hatch and throwing the lot out of the door. So we elected to de- pressurise the aircraft cabin and open the escape hatch in flight – at 43 000ft. Madness or what?

Now, to the best of my knowledge I don’t think this had ever been tried in a Vulcan before at 43 000ft. Perhaps it had been attempted at a much lower altitude but the situation would then have most likely required the rear crew to abandon aircraft due to some life threatening emergency such as an engine or airframe fire.

Neil had already gone to ‘combat pressure’.

“Standby,” said Neil. “Toggles down and select one hundred per cent oxygen on your P masks. De-pressurising in three, two, one, now!

There was a muffled bang instantly followed by a hazy mist in the cockpit that formed as water droplets condensed and cooled under reduced pressure. Our oxygen regulators immediately recognised the fall in pressure and commenced to force-feed one hundred per cent oxygen to our masks. The simple task of breathing and talking suddenly required a major effort on our part. Fortunately our aviation medicine training at North Luffenham had prepared us well; we had all previously experienced the effects of zero cabin pressure and the symptoms of hypoxia at altitude.

The mist had now cleared and I could see Barry and Rod again sitting alongside me in the rear cockpit – that was re-assuring! There was an eerie silence for a moment or two until Barry flicked the power switch under his plotter’s table to open the escape hatch door. A roaring, ear-splitting noise filled the relative vacuum in the cockpit. Imagine driving down the M5 at seventy miles an hour and then opening all the car windows and sun roof and then attempting to hold an intelligent conversation with your partner. Increase that effect three-fold and you come somewhere near to appreciating the environment we now found ourselves in.

Brian Gardner had loaded all our classified planning material, photographic film and crypto into the aircrew ration box and added an undercarriage lock for extra weight. Brian and I then edged the ration box closer to the ‘six by three foot’ escape hatch and pushed it onto the lip of the door as we stared out into the South Atlantic abyss. One extra shove and the ration box slid down the door and disappeared out of sight.

“Clear to close,” I screamed at Barry.

Barry could not hear me over the maelstrom of noise.

“Clear to close the hatch door,” I screamed even louder, again to no avail.

I prodded Barry on his shoulder and gave him a thumbs-up signal and a wave of the palm of my hand in an upwards motion to indicate that he could now close the hatch door. Barry flicked the switch under his table but nothing happened. Then I remembered. The manual operating handle will have now travelled into the locked-open detent position and would need to be unlocked manually. I was still out of my seat standing next to Brian who was by the sixth seat; we both had our parachutes on. I looked across the escape hatch and at the expanse of ocean below and identified the door handle on the far side but realised I could not reach it without a crew ladder fixed onto the door. There was no space on this mission to stow a ladder in its usual stowage position in the nose section adjacent to the visual bomb aimer’s position.

Brian immediately understood what was required. One of us would need to clamber down and straddle the escape hatch and attempt to reach the door handle and dislodge it from its locked detent position. One slip or stumble and it would be curtains. I doubt if either of us would have survived a parachute descent from 43 000ft. What followed was one of the scariest things I have ever done in my life. With my arms wrapped around Brian’s waist we both edged closer to the door. The noise was incessant and we struggled to understand each other over the intercom. Sign language was required to reinforce each message. Brian straddled across the hatch and stretched his right arm forward in an attempt to reach the handle. He was about six inches short. I adjusted my anchor position at the top of the hatch and slid my grip lower down Brian’s torso. The handle wouldn’t budge. It was well and truly wedged into the locked open position. I grabbed my aircrew knife and ripped it from its sheath and handed it to Brian. Brian used the knife to lever the handle out of its detent into the un-locked position. This time Barry’s eyes were firmly fixed on mine and he knew instantly that he was now clear to close the hatch door. No need for a hand signal this time.

Whilst Brian and I had been practising aerobics and pilates on the cabin floor of the Vulcan, Rod had declared an emergency over the HF radio. He had eventually made contact with a Brazilian air traffic controller on VHF 121.5 but the controller struggled to understand fully our predicament and was proving rather un-cooperative. Eventually on UHF 243.0, a more cooperative controller engaged with us but we still did not have his permission to close in on Rio. We continued inbound nevertheless. We had been pressure breathing for a full thirty minutes, which made both internal and external communications nigh on impossible. My suggestion of “tell them we’re from Huddersfield” in a Donald Duck accent gave us that little extra time to communicate with each other on intercom and to handle the in-flight emergency. With the escape hatch now closed and locked we were able to re- pressurise and return to normality. But this was by no means a return to routine ops for us. We had insufficient fuel to make Rio, or had we? It was going to be ‘touch and go’!

Chris Lackman called out the fuel figures in turn from each of the fourteen fuel tanks.

“One thousand pounds, one and a half, two and a half, two thousand.”

Barry totted the figures up and claimed we had clawed back an extra five or ten minutes duration or about forty to eighty miles of range. It looks as though the cruise climb to 43,000ft has helped but then the drag from the open door hatch won’t have assisted much either.

Now, unbeknown to us until well after we had landed, the Brazilian air defence commander had scrambled two Northrop F-5s to intercept us. We never did learn what their intention was or what action they would have taken had they found us. Fortunately, the duty fighter controller vectored the pair to the wrong location and so the nearest they got to us was when we were short finals to land. To catch us up they had to turnabout and accelerate to Mach one plus, which resulted in one F-5 delivering a supersonic boom over Copacabana beach and the bay of Rio.

Our voices were by now sounding a little more confident and the Brazilian controller had accepted that we were not going to turnabout and disappear out of his sector. We were now his problem for the day. Neil commenced a gentle cruise descent with about sixty miles to run and levelled off at 23,000ft. By now I had identified Rio International Galeão airport on the H2S radar and provided an accurate steer to the flying pilot, Neil.

“We are not going any lower until I can see the runway threshold with my own eyes,” exclaimed Neil.

Fortunately the visibility was superb that day and there was no cloud cover whatsoever. Provided the fuel holds out we should be able to spiral down almost in the overhead with the throttles at idle. This was the plan. Were the engines to flame out now then we would still have a good chance of being rescued off the coast. The sea was fairly warm and so I could now dispense with my immersion suit.

We still did not have authority to land but we were going in anyway. We were talking to a controller and we were squawking emergency on the IFF. We had a radar service. The controller could provide safe separation and de-confliction for civil airliners in our vicinity. We crossed the coastline at 16,000ft and commenced a corkscrew descent, a full thirteen and a half hours after departing Ascension Island. The controller finally gave us permission to land on the duty runway but that would have required a risky, downwind over-flight of the city to reach the runway threshold. We could not afford the engines to flame out over a highly populated area. Neil elected to land on the reciprocal runway, downwind, rather than into a light, five to ten knot breeze.

“Let’s get the gear down now,” said Neil.

We were now committed but Neil still needed to nail the approach parameters, and we were currently too ‘hot’ and too high at 10,000ft. The fuel gauges, according to Chris, were now indicating empty across all four groups. This was going to be close! Neil eased back on the throttles, extended the airbrake and bled the speed off. Chris pushed the gear ‘down’ button. One, two, three greens. That was a relief. Neil then stood the bomber on its port wing-tip and pulled it into a tighter two to three G turn with sixty-five degrees of bank. His concentration was now entirely focussed on making sure he would nail the parameters as he approached the high and low key positions from an approach that did not feature in the aircrew manual or flight reference cards. This was the only way Neil could trade off height against speed without exceeding the incipient stall. He needed to get the big bomber on to short finals with about 130-135 knots of airspeed. Neil was right on the money. A superb piece of skilful flying and airmanship ensured he was able to roll out on the extended centre line of the runway at three hundred feet with about one mile to run. For this and the part he played in Black Buck 6, Neil McDougall was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The minimum landing fuel in peacetime after diversion for a Vulcan was 8,000lbs and for operational flying 4,000lbs; the fuel gauges were notoriously unreliable. A full visual circuit required 1,700lbs of fuel. We cleared the runway, stopped short and Rod slid out down the escape hatch door onto the taxiway to disable the Shrike missile, just in case! As we taxied onto a hard standing on the military side of Galeão airfield with only fifteen hundred pounds of fuel remaining, one of the four Rolls Royce Olympus 301 engines flamed out!

At Galeão we were greeted by forty to fifty armed guards along with their base commander, and were held under open arrest in the Officers Mess for a period of seven days. We were well treated and cared for and were invited to a squadron BBQ and allowed to participate in a daily five-a-side football competition (which the Brazilians always won of course) but we were not allowed to leave. We each took it in turns to guard and watch over Vulcan XM597 for the whole time we were there. The remaining Shrike missile was confiscated by the Brazilian Air Force and taken to an armoury. We unloaded the missile ourselves using a hydraulic safety raiser with a mattress from the Officers Mess laid on top, after making it safe with pylon pins and its own missile safety breaks. We were still a little concerned that a firing pulse may have travelled down the pylon and launcher unit and had initiated part of the missile launch sequence. Fortunately it hadn’t. The British Air attaché from Sao Paulo took charge of our release negotiations but the Argentineans had already made a request via the Brazilian authorities for us to be handed over to them as prisoners of war. This request was politely refused. Eventually, diplomatic pressure was brought to bear but the real reason we were released, according to the Brazilian colonel who was assigned as our mentor and escort, was that the day after our eventual release on the 11thJuly 1982, Pope John Paul ll was travelling to visit Buenos Aires. On his way to Argentina, arrangements were rapidly being made for him to fly into Rio Galeão Airport where he was expected to say Mass to an invited congregation of nearly a hundred thousand followers. The altar for Mass was to be located on the hard standing next to where our Vulcan bomber was parked. The base commander requested that we taxied 597 to the other side of the airfield so that it would be out of sight. We politely declined but suggested that if he filled our tanks to full with AVTUR we would get out of his hair and fly back to Ascension forthwith. Our request was granted, probably to save embarrassing the Pope or the President – or both.

That afternoon the Brazilian Chief of Air Staff visited us to wish us well before our planned departure the following day. He asked what we thought of Rio but we replied that we had not been afforded the opportunity to taste or experience the delights it had to offer. He was shocked to hear this and immediately ordered the base commander to task one of his Super Pumas to take us on an aerial sight-seeing trip of Sugar Loaf Mountain and the beautiful coastline of Rio. He then ordered our colonel escort to arrange for a taxi to take us down town to a cabaret show and a few farewell beers. We were aircrew. How could we possibly refuse his invitation? Neil our Captain though correctly elected to stay with his bomber.

Without going into too much detail, we had a romping good time down town including being propositioned a few times along the strip between Copacabana and Ipanema beaches. Two girls in particular proved difficult to shrug off. One had an Australian accent but claimed to be Argentinean. We were naturally very suspicious and tried to keep her at arm’s length. It wasn’t until thirty years after this event that I learned who this girl and her colleague really were. When the Foreign Office had learned that the crew of Black Buck 6 was about to hit the town before being released back to Ascension Island, someone in the Ministry of Defence must have had a fit. He was probably ex-aircrew himself and knew of the potential pitfalls that could await unsuspecting aircrew after being incarcerated in an overseas mess for a whole week. After all this was a foreign country some five thousand miles from the UK. Britain did not have any MI6 operatives in the area at the time and so a request was made to the CIA to put a tail on us, mainly for our own safety as who knows what could have happened to us that night as we sauntered around town from one cocktail bar to the next. There is one thing I can say and definitely vouch for though. Rio is a hell of a long way from Huddersfield.

On leaving the V-Force, Wing Commander David Castle went on to realise his ambition by completing three tours on Buccaneers at RAF Lossiemouth. He became a Qualified Weapons Instructor and was appointed the Senior Navigation Instructor for No 237 Operational Conversion Unit. He carried out 17 missions during Gulf War 1 in the Pavespike laser designation role and retired from the RAF in 2005 after 32 years of service.

Having recently joined the Guardian Squad I thought it might be an idea to put on paper, my contact with the Vulcan, during my RAF

Saturday 29th September, was the day of XH558’s final flight for 2012. It was a day that, for those of us who fly the aircraft,

As XH558’s 50th anniversary year approached, funding was an issue once more. During 2009, the Vulcan had flown for some 50 hours (over 30 sorties),

Every year at Wellesbourne Mountford Airfield near Stratford on Avon the XM655 MaPS (Maintenance and Preservation Society) team of Vulcan enthusiasts who look after Vulcan