Ramblings from the AEO’s Panel – Part 6

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a key

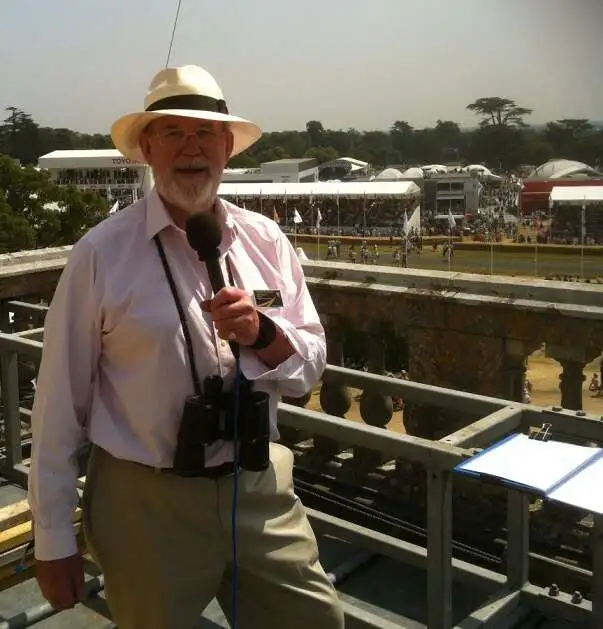

Well-known and highly respected air show commentator Seán Maffett became synonymous with Vulcan displays and indeed was the official commentator for the Vulcan to the Sky Trust during the eight years of post-restoration flight by XH558.

Some of you may also recognise his name from his many radio and TV broadcasts, particularly on the BBC. With a past steeped in aviation, his personal life held a tragic story. Written in 2016, Seán shares his quest to find out what happened to the father he never really knew. In this most candid and emotional of stories, Seán reveals the background.

Sean in action at Goodwood.

My mum died nearly eighteen years ago, with a broken heart. During the Second World War, she, like many other wives, had found her world starting to collapse when my dad, John Maffett, was declared ‘Missing in Action’. But it was all made much worse when her father-in-law took a mysteriously deceitful, drastically wrong decision that deprived her of solace and comfort.

Mum survived to be 87, so she had a good innings, but the intervening half-century did nothing to heal her pain.

Mum had refused to believe that the love of her life was dead. She expected him to walk back through the door any day. She never remarried, and I don’t believe she ever had a relationship with another man.

I’d been eleven months old when Dad went missing. For the duration of my childhood, there were just the two of us, Mum and me. I never knew my dad, but he was, of course, a hero to me.

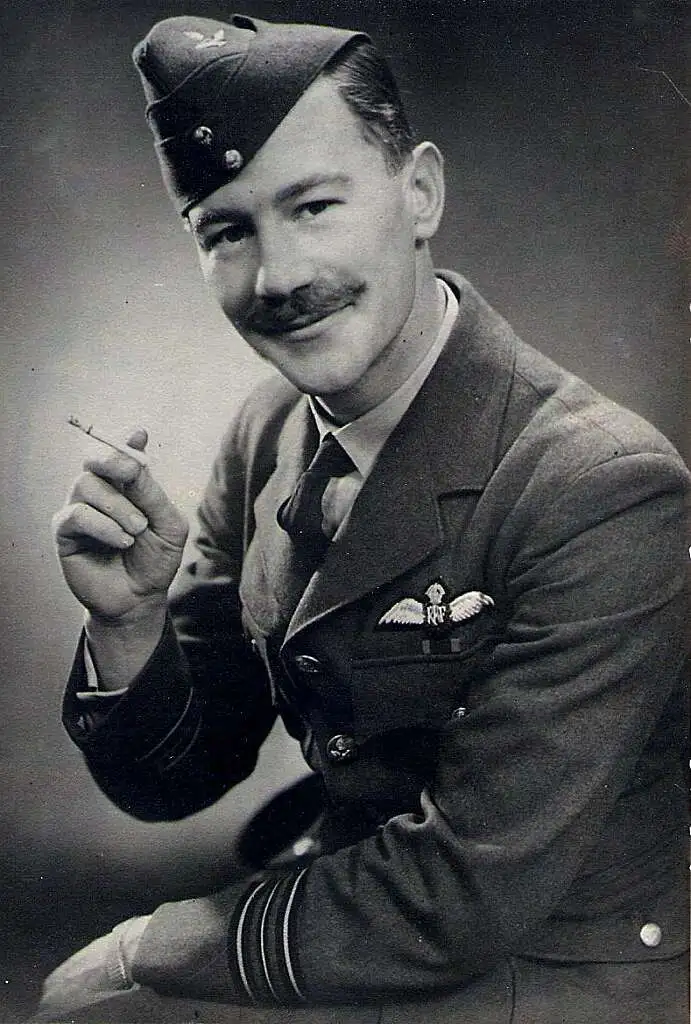

In February 1942, 29 years old, Dad had been a newly promoted Wing Commander in the RAF. Months before, he’d changed from flying single-engined Lysander reconnaissance aeroplanes to the twin-engined, long range Beaufighter. He was posted to North Africa, almost certainly to command a Beaufighter squadron, No 46, then stationed at an aerodrome called Kilo 17, near the Egyptian border.

He and another pilot, Sergeant Brian Smith, and Flight Sergeant Harry Sprason, a wireless operator, were flying there, in a Beaufighter. They’d got to Gibraltar, and departed for the 1,100-odd mile flight over the Mediterranean to Malta. Apparently, they never arrived. Sad to say, that was not an unusual event then. And, unless you were very lucky, you were unlikely to be rescued, even if you survived ditching in the sea.

The three of them were presumed dead.

John Maffett in RAF uniform.

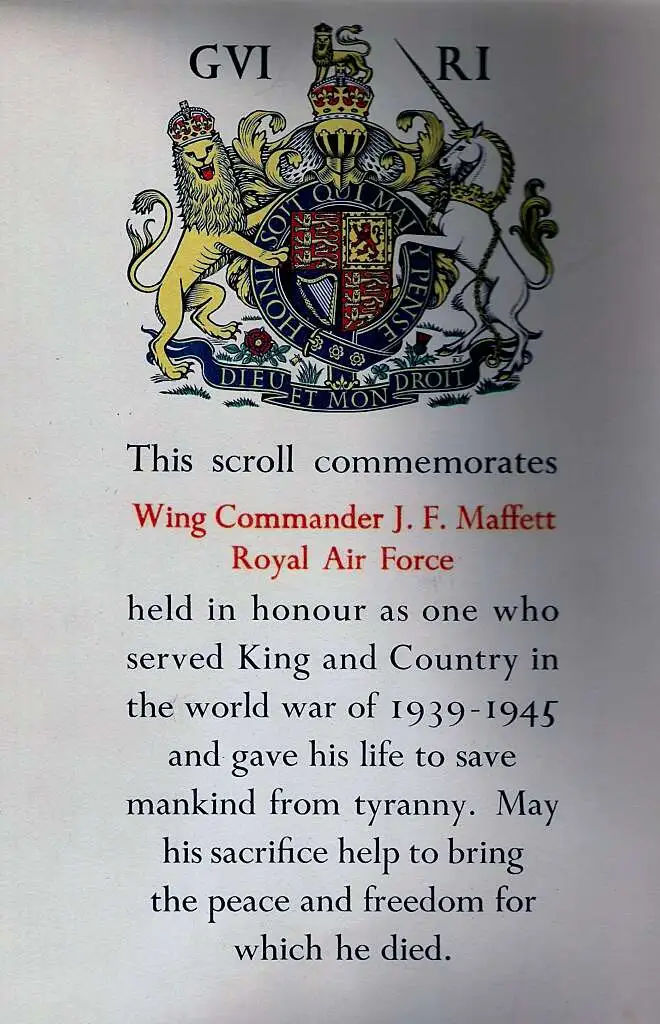

Obviously, there was to be no burial for them. Years later, they were commemorated, along with 24,400 other airmen and women, at the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede for those who have no known grave. Mum and I went to see the Queen open the memorial in 1953. I was twelve, and I was immensely proud of my dad. Mum didn’t seem too affected by the occasion – but then, she didn’t think he was dead. She was just quietly proud.

My grandmother used to refer to Mum as “your poor dear mother”. But, like many of her generation, Mum kept her feelings to herself. She and I never really talked much about Dad – and even that seemed quite normal.

Not having a dad seemed equally normal to me, and I grew up intending to join the RAF as soon as I could. People were always telling me how like my dad I was – even to the surprising extent of having some of his mannerisms.

When I finally left home at seventeen to join the RAF, Mum didn’t try to stop me. And she seemed resigned to the prospect of a life alone, harbouring her secret hope that her John would come back to her.

Seán with his mother in this family portrait.

I remember one strange social occasion. I was introduced to a very genial retired RAF officer, a man I’d never seen in my life. He said “Seán Maffett – your middle names are Hamilton Alex!” Taken aback, I agreed, except to point out that they were the other way round – you probably wouldn’t want the initials ‘SHAM’. He said “I remember your dad coming into the officers’ mess bar at (RAF) Odiham and saying ‘It’s a boy!‘ We all drank your health.”

Neither my mum nor I could know that time was ticking away for some possible relief for her broken heart.

Nowadays, I can’t understand why I didn’t question her sooner about her life with Dad. By the time I’d got round to it, after I had left the Air Force, she had Alzheimer’s disease, and her memory was going. In the last months of her life, she was hardly aware of who anybody was – and I was developing a belated, and desperate, need to find out more about Dad.

I did talk to my uncle, Dad’s youngest brother. At the start of the war, he’d been a subaltern in the Royal Artillery. He’d found himself in France, commanding an anti-aircraft battery. It was his 21st birthday. He was surprised to see an RAF Lysander fly over. It turned out to be Dad. He’d flown across the Channel from Odiham in Hampshire. He’d circled round, and dropped a standard military message pack with those long multi-coloured cloth streamers. The message inside just said “Happy 21st. John”. My uncle never did find out how he knew where the gun battery was. It was supposed to be secret.

For some strange reason, I hadn’t previously thought to ask the RAF about Dad. But when I did, their Air Historical Branch overturned our understanding of what had happened.

Far from going missing somewhere on that long flight from Gibraltar, Dad and his two colleagues had arrived safely in Malta. Having rested and refuelled, they took off again, presumably to go to Kilo 17. As they flew out over a little rocky outcrop called Filfla, three miles off Malta, they were bounced by two German Messerschmitt 109 fighters, almost certainly from Comiso in Sicily. All three aeroplanes disappeared out to sea. Nothing more was heard from Dad’s Beaufighter.

Other aeroplanes and a high speed launch made extensive searches, but they found no trace of the Beaufighter or its occupants.

After the war, the Missing Research and Enquiry Unit checked with the International Red Cross. Finding nothing, the Unit confirmed the presumptions of death. Because no bodies were found, the three were officially classed as ‘Missing’.

But it seems clear that they did die on that day, 12th February 1942.

The Air Historical Branch showed me a copy of a letter from the Air Ministry to my grandfather explaining the contemporary understanding of what had happened. So why had my grandfather chosen to tell us all something quite different? No one knows.

Just possibly, it might be related to the fact that, eighteen months earlier, Dad’s younger brother – the middle of the three sons – had been killed flying a Hurricane in the Battle of Britain. Perhaps, after not one, but two such unbearable losses, my grandfather thought to protect his family with a different story. I have to say, though, that I can’t make sense of it.

I really wanted to tell Mum what had actually happened, and at least give her the relief of what we now call ‘closure’. But it was too late. She had retreated, incommunicado, into her Alzheimer’s fastness. She died shortly afterwards, not knowing what had really happened to her beloved John.

I believe I have recently discovered the name of the German pilot who shot them down. If I have the right man, he himself was shot down and killed the following year. Naturally, I bear him no malice.

As a postscript, I did eventually find my own crumb of comfort. Three years after Mum died, my wife and I went to Malta. The Armed Forces of Malta had kindly arranged for us to fly in a helicopter to the nearest estimate of where the Beaufighter had gone down.

We flew out past rocky little Filfla. The small Alouette helicopter came to the hover, perhaps twenty feet above the Mediterranean. The downdraught from its rotor flattened the waves in expanding circles. The crewman opened the door. He stood back and saluted, as I leant out and dropped a velvet bag containing precious mementos into the sea.

I’d put in pictures of Mum and Dad together, and of my wife and children; also Dad’s rugby cap, and my RAF cap badge. Then there was Mum’s death announcement from the Telegraph, which talked about their being together again, dancing the sky on laughter-silvered wings.

Oh, and there was one of Dad’s favourite things – a pewter beer tankard.

I can feel the tears welling up just thinking about it. I just wish I could have told Mum.

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a key

On Saturday 30 August 1952, history was made as Avro Type 698, VX770, took to the sky for the first time. It was the prototype

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a key

Barry Masefield was the Air Electronics Officer (AEO) for Vulcan XH558 and had flown in this iconic aircraft for over 30 years, also being a key