1955-1959 – Vulcans in Service

From the time of their arrival into service at the Operational Conversion Unit (OCU), all the Vulcans were painted silver, but in April 1957 the

An espionage story from 1966 – by Jim Debenham, VTST Volunteer

If this were a fictional story it would have been written by none other than Ian Fleming, with James Bond as the lead character.

During the heady days of the Cold War one of the most important buildings in Berlin was the British Military Mission in Potsdam. This was the headquarters of British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany (BRIXMIS), an autonomous unit roving around the Soviet sector like anonymous buccaneers assisting with defections and monitoring Soviet troop and vehicle movements.

At the height of the Cold War in 1966, when the whole of Britain was rocking along with The Beatles and looking forward to the World Cup, the government of the day feared that Britain was teetering on the brink of nuclear annihilation as the US and NATO had some 8,500 nuclear warheads based in Britain and Western Europe, whilst the Soviet arsenal numbered just over 7,000.

Both sides were holding huge military exercises close to each other’s borders to test out various nuclear options and World War III scenarios. At this time in Moscow, Washington, Paris and London, world leaders were wondering if this could be a prelude to World War III.

During these military exercises a more secretive and disturbing sequence of events was taking place in the skies above Berlin, events that led to the loss of several US aircraft and crew. At the time the official explanation was that these aircraft had strayed off course into Soviet airspace and had been deliberately and callously shot down by Soviet anti-aircraft fire. But these casualties were not accidental intrusions, they were carefully planned; the aircraft and crew would become Cold War sacrifices.

Before each flight, the secret listening post at Gatow Airfield were ordered to monitor the Soviet defensive frequencies to see how fast the Soviets spotted the intrusion and how quickly they could react. This became a deadly game of Cat and Mouse.

At the time NATO believed that the Soviet YAK-28p was the reason that so many aircraft were shot down. The NATO code for this aircraft was the Firebar, very little detail was known about the aircraft. Information from spies (BRIXMIS) around the Soviet sector was very sketchy and had only resulted in a few grainy photographs. Information from pilots, who had experienced incursions from this aircraft, could only confirm it could fly at supersonic speeds and to an approximate ceiling height of 60,000 ft., this however was not enough to explain the Firebar’s superior combat performance.

Amongst pilots it quickly earned the nickname The Shark of the skies.

What made this aircraft so superior was a mystery to NATO until April 1966, when the answer was found at the bottom of Lake Havel in the British Sector of Berlin.

Berlin during the 1960s was the one of the most military sensitive places in the world. Trapped in a sea of Soviet occupation, it was governed by the four superpowers. The Soviet Union controlled the entire Eastern sector, whilst Britain, France and the United States shared control of the Western section.

Berlin was also physically divided by a concrete and barbed wire wall guarded 24 hours a day by Soviet machine gun posts and an area peppered with landmines. The wall separated East and West Berlin and Berlin from the rest of East Germany.

The relatively tranquil setting of Lake Havel in the British sector offered a welcome respite from the Cold War tensions. The people of West Berlin visited the lake to sail, fish and relax. But on April 6th, 1966 at 3:30 in the afternoon, as Berliners were preparing for the Easter holiday, the peace and tranquility of Lake Havel was shattered as a Firebar with both engines flamed-out, crashed nose down into the lake.

An eye witness on the day said they had seen what they thought was a model aircraft in the sky but as the aircraft got nearer and bigger they could see the Soviet red stars on the side of the aircraft and could tell from the sound that the engines were obviously not working correctly. As the aircraft got nearer to the water they could clearly see the two pilots and wondered why they were not ejecting from the aircraft.

A second eyewitness said the aircraft was gliding silently and getting lower and lower until eventually it plunged into the water about 250m from his boat.

The Listening station at Gatow Airfield had been tracking the crippled YAK-28p from several miles away. When they realised the aircraft was down the local commander contacted the Berlin fire brigade to attend.

Three detachments of the Berlin fire brigade attended and when they arrived at the lake could see little or no evidence of a crashed aircraft. Then one of the commanders noticed what looked like the tail fin of an aircraft sticking out of the water in the middle of the lake, but at this point they were unaware if the pilots were still in the aircraft. What quickly became obvious was that even if there were people on the aircraft, they were in no position to help.

Members of the Press had heard about the crash and started to appear on the banks of the lake. These were quickly joined by the British occupying forces who speedily cordoned off the crash site. Shortly after this several Soviet officers appeared and were enraged to find that they could not get access to the crashed aircraft.

BRIXMIS Russian speakers were ordered to the lakeside to help with interpretation as the Soviet officers were getting increasingly distressed at being denied access to their aircraft.

As the aircraft had crashed in the British sector, it was up to the British to arrange recovery, and return the aircraft to the Soviets. This would be coordinated by the British military mission (BRIXMIS) who were the military liaison with the Soviet authorities in East Germany. Brigadier David Wilson and his team set about planning an operation to recover the aircraft – a project which was to become very secretive and tense.

During the next few hours activity around the crash site became very frenetic. 38 Engineer Regiment started by putting huge barges, used for transporting large equipment and vehicles across lakes and rivers, around the crashed aircraft.

During those few hours a large contingency of armed Soviet troops had arrived at the lakeside. Things were beginning to get heated as the Soviets did not want the British to have access to the aircraft.

Crucial to the operation was identifying the crashed aircraft. BRIXMIS Squadron Leader Maurice Taylor rowed out to the aircraft in a small boat to take pictures of the tail fin and gather as much information as he could. On the bank the Soviet troops were watching him do this and becoming increasingly more agitated, as they saw it as their responsibility to recover the crashed aircraft. The Soviet view was that even though the aircraft had crashed in the British sector it had to be recovered by them, by force if necessary.

The atmosphere now became very tense and it became obvious that this was no ordinary aircraft.

Back at BRIXMIS headquarters in Potsdam, the camera film taken by Squadron Leader Taylor had being processed and passed to Junior Technician Eddie Batchelor whose role it was to identify the aircraft. Eddie went through every manual available to him to try to identify the mystery aircraft but came up blank. He remembered a few days earlier that the Americans had just supplied them with some new , and when he sifted through it he found details about the YAK 28p, with the tail plane clearly showing the same aerial as on the aircraft in Squadron Leader Taylor’s photographs. This was the Soviets latest and most prized attack aircraft.

Immediately an urgent coded message was sent to the Defence Intelligence secretary at the Ministry of Defence in London. The reply was to trigger one of the most audacious intelligence gathering operations of the Cold War era.

Back on the lakeside armed Soviet troops were now stood face to face with British forces, East and West were just one command away from conflict.

Meanwhile at the British mission headquarters Peter Hayman, the British Garrison Commander, refused to be intimidated by the Soviet action. He dispatched a letter to the Soviet Commander, General Romanov, at the lakeside demanding that Soviet armed troops be removed from the British sector or consequences would follow.

Upon receiving the letter Major General Bulanov asked “Is your commander threatening the Soviet Union” to which the answer was “Yes”. Tension was rising higher by the minute.

Fortunately Major General Bulanov’s next move was a more conciliatory one. He ordered his troops to back off from the lakeside leaving only a small contingent of senior officers and a couple of diplomats to observe the proceedings.

Even though the General had withdrawn his troops, the prize was still not guaranteed, but tantalisingly close, as lying on the bed of the lake was Soviet technology never seen by the West.

To uncover the crashed aircraft’s secrets two separate missions were planned. One plan was a clandestine operation to recover the Soviet secrets from the bed of the lake, the second was a bluff to buy time for the first plan to succeed.

Divers had made a preliminary inspection of the aircraft and confirmed what the listening station at Gatow had said, that the pilots had asked for permission to eject and were told “No you must stay with the aircraft”, as they were found dead and still in the aircraft.

From the tracking data it appeared that the pilots were trying to land at Gatow. With a flame out they could not get that far, so they made the decision to crash into the lake rather than the populated area between the lake and Gatow, which would have caused hundreds of casualties.

In order to recover the dead pilots from the aircraft, divers would first need to make safe both ejector seats, as they contained explosives which if detonated in the water would have killed anyone nearby and destroyed the aircraft’s precious cockpit technology.

The dive team that was put together included an RAF armorer who was to dive down to the aircraft, disarm the seats and check for any weapons on the aircraft. As this was secret Soviet technology, they had no idea what to expect.

The dive team found that the aircraft was not armed and just required the seats to be de-commissioned. As this was different technology to what the RAF had, the diver ended up using various nails and screws to make the seats inoperative.

Whilst all this was taking place tension on the lakeside was growing. BRIXMIS interpreters were passing on crumbs of information to the Soviets who were getting more and more concerned as the British would not confirm whether the pilots had ejected or not. The thing they feared the most was that the pilots had left the aircraft and were now somewhere being interrogated and giving up all the aircraft’s secrets.

Frustrated, the Soviets had now decided to bypass BRIXMIS and ask questions through diplomatic channels, but the British had already anticipated this.

Squadron Leader Dorren was on the 7th hole of the golf course just teeing up to take his shot, when a dispatch rider raced across the golf course on his motorcycle with an order for him to return to headquarters immediately. He was, at that time, the only military diplomatic contact between the Soviet and British forces. He was the only person the Soviets could approach to make a diplomatic complaint. Upon his return he was swiftly ordered to go out to the barge in the center of the lake and supervise the recovery. This was a clever ploy used by the British to stop Major General Bulanov having access to the diplomatic channels and raising a diplomatic complaint.

During this time, with the ejection seats safe, the dive team could remove the bodies of the two pilots. This was done under the secrecy of darkness, and the bodies were passed on to Western intelligence who photographed every document they were carrying and recorded the details of all their personal possessions. At this point the Soviets were told that the pilots were still in the aircraft and had been found dead. However, as the ejector seats still needed to be made safe their bodies could not be recovered yet. This was a classic stalling tactic to buy time.

Immediately the Soviet commander said they would need to be involved in the recovery operation because only they could make safe the ejector seats. This was a ploy by the Soviets to allow them to recover the aircraft radar, which was the secret installation they were desperate to protect.

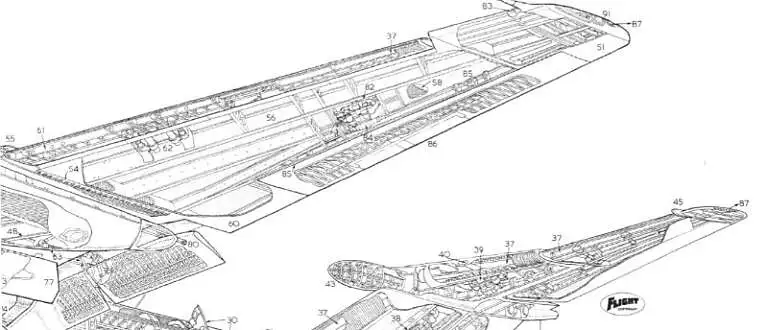

Any of the technology fitted to this aircraft would have been interesting to British Intelligence, but this aircraft was special as it was carrying a new type of radar. Traditionally an interceptor would have had a fixed radar dish which could only look forward in a straight line. Fitted to this aircraft was a new system which the Soviets had developed, which would allow the aircraft to not only look in a straight line but also look upwards. This gave the pilot the opportunity of fixing on a target in front of his aircraft, and then searching above his aircraft for a second target without having to alter the attitude of the aircraft, thus giving the pilot the opportunity of two targets. The chance to get hands-on with this type of technology was not to be missed and could be the crown jewel in any future conflicts with the Soviets.

Back on the lakeside, having been on the barge for quite some time, Squadron Leader Dorren decided to return to shore. Upon his return, Major General Bulanov immediately demanded a meeting with him. Squadron Leader Doren invited the Russian Commander to take a seat in the rear of his staff car. At this point Major General Bulanov got very heated having been kept waiting a long time to make his diplomatic protest. But before he could make his protest Squadron Leader Dorren stopped him in his tracks by announcing he wished to make a diplomatic protest about the Soviet Air Force flying aircraft across British airspace and therefore endangering British and West German lives. Having been usurped by this protest, Major General Bulanov, knowing he had been trumped, swiftly exited the car slamming the door.

Having been diplomatically beaten, the Soviets decided all they could do was watch the recovery of the aircraft. In order to do this clearly they brought in a large military searchlight. The brightness of this light made it very difficult for the recovery teams to work, so a message was sent to the Soviets stating that unless the light was switched off all recovery work would stop. After a short time Major General Bulanov reluctantly ordered the light to be switched off.

Shortly after this another barge was brought alongside the wreckage. This barge had a large screen which stopped the Soviets from seeing any activity carried out. The Soviet officers accused the British of dismantling the aircraft behind the screen and taking photographs of its sensitive equipment. The senior officer at that time categorically denied this, just as several flash bulbs went pop and the sound of heavy hammers could be heard banging on the aircraft.

As British Intelligence had finished with the two dead pilots, in order to quell the tension the British offered the return of the two pilots’ bodies. On hearing this, Major General Romanov asked if a barge could carry a band out to the aircraft, so as to play the Death March as a mark of respect to his two fallen comrades. The British commander knowing that he had to covertly put the crew back in the water and that this was just another way of the Soviets getting troops out to the aircraft had no choice but to say “No”, which again raised General Romanov’s blood pressure to bursting point.

This was a dimly lit affair that took place in almost darkness. After the pilots were covertly returned to the aircraft, they were then brought to the surface in plain sight of the Soviets. The bodies were recovered from the aircraft and laid out on a barge covered by the Soviet flag. They were then taken to the bank and handed over to the Major General Romanov who insisted their faces be uncovered so they could verify the identity of the two pilots. This all happened at midnight on the 8th of April. The two pilots were ceremonially loaded into a hearse, watched by an honor guard of Soviet and British troops whilst a lone Piper played a lament in the cold night air. The bodies were then returned to Moscow where they were given a hero’s funeral for making the ultimate sacrifice and not leaving the aircraft (a brave but ultimately needless act).

The aircraft was demolished piece by piece, revealing all of its secrets. All of its parts were being drawn or photographed for future analysis; all this was being done under the watchful eye of the four or five senior Russian officers with binoculars on the bank.

Under cover of darkness the engines from the Firebar were winched off the lake bed and inspected by British Intelligence. One of the engines was strapped beneath a small boat and taken a couple of miles down the lake to a local yacht club, where it was placed in a container ready to be sent back to Britain. The following day it was taken to the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough. It was stripped down, analysed, and then reassembled and shipped back to Berlin all within 48hrs, to be reunited with the aircraft.

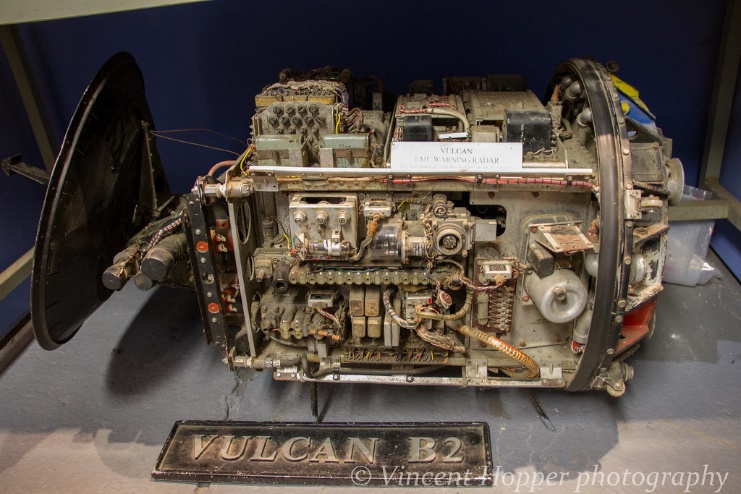

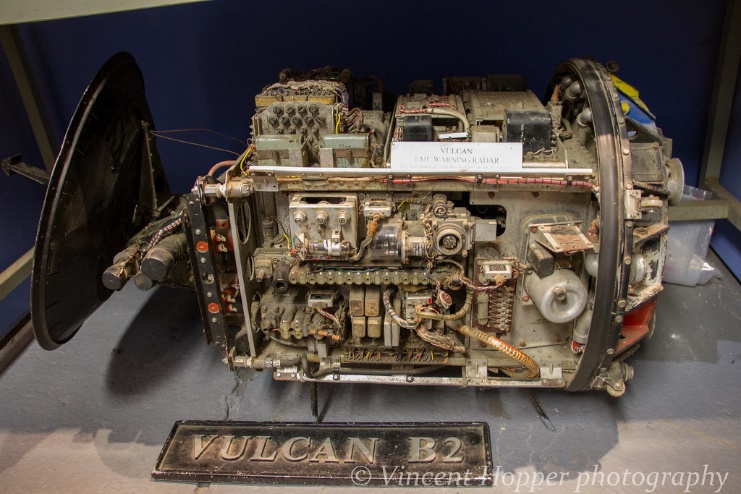

The crucial piece of equipment the engineers needed to see was the new radar system known as Skip Spin. Again, this was removed from the aircraft, strapped underneath a boat and transported to the local yacht club, where again it was placed in a container ready to be sent back to Britain but never to return.

With the recovery phase now complete it fell to BRIXMIS to return the aircraft to the Soviets. An inventory of parts recovered was created and a certificate issued to the Soviets to say that recovery work was now complete and “the British had returned all the aircraft”.

As the Soviets started to inspect the parts they freely admitted that the crash had in fact been catastrophic, but they said “a large part of the aircraft is missing”. BRIXMIS responded with “we have no idea where it is, or what you are talking about”. The view taken was, as this was a secret piece of equipment the Russians were hardly going to kick up a fuss. The Soviets insisted that parts were missing so asked for the certificate and inventory to be changed and for the wording to say “the British say they have returned all of our aircraft”.

Let’s not forget as a consequence of this crash, possibly hundreds of lives were saved by the bravery of the two pilots who, by not ejecting and instead controlling the crashing aircraft, avoided hitting a major population center.

Had they managed to land at Gatow, the worst that would have happened would have been protests between the Soviets and British, but ultimately the aircraft would have been handed back without the British even getting a look inside.

As a result of this successful operation, the Vulcan Bomber, which was Britain’s main-stay strategic nuclear bomber at the time, was fitted with anti-Skip Spin measures incorporated into its Red Steer tail warning radar enabling it to jam and counter the best Soviet radar of the day.

This could only have been developed as a result of being able to analyse the Soviet technology from this crash.

Thankfully the Cold War ended without it ever being used in anger between the two sides.

Credit and our thanks for this story go to Eddie Batchelor (BRIXMIS Retired) who brought this story to our attention. Eddie was the Junior Technician in the story and a real-life James Bond of the Cold War.

From the time of their arrival into service at the Operational Conversion Unit (OCU), all the Vulcans were painted silver, but in April 1957 the

Vulcan to the Sky volunteer Geoff Higley, who lives in Grantham, was in the airforce for 20 years as a navigator. Here in our Q and A

On 28 October 2015, over 55 years after her first flight, Avro Vulcan XH558 – the world’s last airworthy Vulcan – flew for the final

Dr Steve Liddle CEng FRAeS, is a Vulcan to the Sky Trustee and Principal Aerodynamicist at Aston Martin Formula One Team. The articles here are